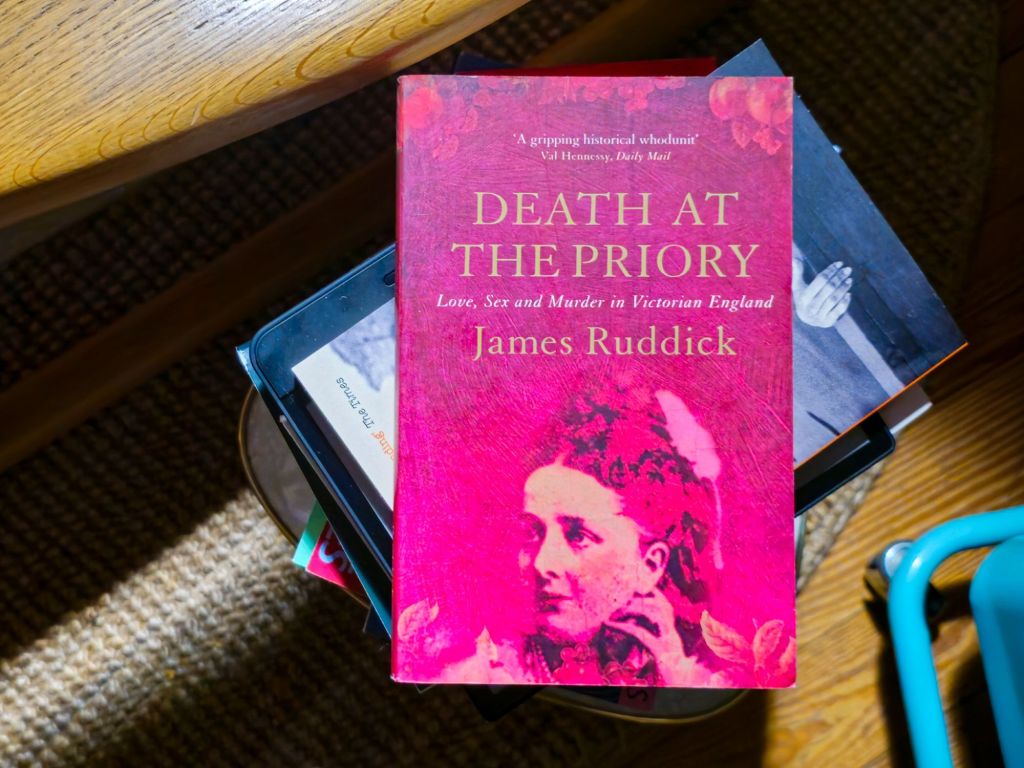

Ruddick, James (2001), Death at the Priory, Atlantic

ISBN 1-903809-44-4

The Charles Bravo case is a well-known mystery for True Crime enthusiasts. You may have encountered it in one of the countless books or TV shows that explore its details. In 1876, Charles Bravo died of poisoning, and four suspects emerged: his wife Florence (in her second marriage), her housekeeper, her former lover (a distinguished doctor), and a former stableman. None of them were convicted of the murder, but their complex sexual histories were exposed. Agatha Christie called it “one of the most mysterious poisoning cases ever recorded.” The case remains unsolved to this day, and James Ruddick’s book is not a definitive answer, but an (at the time) new addition to the ongoing speculation. This review will be brief, as I have no intention of reading the other 20 books on the subject. I should also note that this book is mainly for those who are unfamiliar with the case, or only know it superficially. If you have already read more than 2000 words on it, or watched a TV show that came out after this book, you can skip it. Ruddick’s writing is good, and the structure is excellent, but the main merit of this book is the presentation and organization of the facts. This is no Alias Grace, but a concise 200-page account of a fascinating case.

That said, if you, like me, are new to the cause Charles Bravo – this is an intriguing entry into the historical True Crime canon. There are some drawbacks to the book – the story of a woman’s desperation, repeated abuse, and rape at the hands of two different husbands, and her potential decision to clear up this situation by poisoning the second of the two should not have been written by a white male writer who isn’t particularly attuned to the situation (although he tries). But it is rare to read a book that is written with such a supple and readable prose, while at the same time keeping a tight lid on the proceedings. There is a little narration, a little psychological speculation, and quite a bit of in situ self inserts – but at 200 pages, we are offered the full facts of the case, and a broad (if occasionally misleading) summary of the various theories. Ruddick’s final explanation isn’t different from others already offered, but if you are new to the subject, it makes for engrossing reading, you get a sense of the entire situation, and Ruddick’s personal biases, though enormous and unstated, are so incredibly glaring that they do not block the view of the entire situation.

I will not go into the details of the case and the motives for suspecting any of the usual culprits. But Ruddick’s treatment of the two main suspects reveals his biases. They are the widow and her loyal servant. Ruddick, writing in 2001, provides a sympathetic context for the hardships of Victorian women. He frequently mentions the abuse they endured, especially Florence, Bravo’s widow, and their lack of options. He repeats these contexts after his conclusion. For Ruddick, misogynist abuse is woven into the story. Yet, we read about Florence being raped repeatedly, without Ruddick ever calling it that explicitly. He depicts different types of marital sexual intercourse, but they are all forcible rape, meant to dominate Florence. He even implies that Florence was raped to coerce her into marrying Charles Bravo. His failure to label every sexual act between Bravo and Florence as rape creates complexity and ambiguity where there is none. And there is more: during her first (abusive) marriage, in her 20s, Florence receives treatment, and soon starts an affair with James Gully, the sexagenarian doctor who runs the facility. Florence describes this relationship as consensual, but the ambiguity about the power abuse in the second marriage casts doubt on Ruddick’s ability to assess the consent in this affair.

Here as everywhere else, Ruddick is hesitant to offer a truly fundamental critique of the situation, which also blocks him from seeing other motives for Florence’s housekeeper Jane Cox. Her motives historically tend to be viewed as financial in nature, and Ruddick deals with that, but the alternative is entirely ignored. That alternative consists in seeing her mistress raped regularly and seeing her switch from a situation with dubious consent to a situation with no sexual consent whatsoever, which might work as motivation for someone with a strong sense of community and care. In fact, the connection between the two women, which entirely escaped James Ruddick, is so woven into the material that Shirley Jackson, whose novel We have always lived in the castle is inspired by the Bravo murder case, was troubled by the possibility of having written a lesbian narrative. Ruth Franklin, in her excellent memoir of Jackson, cites a letter, in which Jackson refers to that possibility as a fear of being seen (even by herself) as a lesbian. “[The novel] is about my being afraid and afraid to say so.” Jackson, unintentionally, saw a deeper connection in the case than Ruddick, despite his stated years of research in archives.

That said, the biggest blind spot to the book isn’t in the analysis of the case in the strict sense at all. It is in the overall contextualizing of the sexual politics of it. This would be a bigger essay – but there are some odd asides that Ruddick never follows up on. Jane Cox, the housekeeper, eventually inherits a huge plantation in Jamaica. And she’s not the only character with a family connection to the West Indies. Ruddick, towards the end of the book has a brief chuckle about some coincidences: “The family of James Gully, for instance, owned coffee plantations near Kingston, Jamaica, while Charles Bravo’s family had originated in Kingston and had made their money from exporting the coffee grown by Gully’s grandparents. Later, the Bravos had moved to St Ann’s Bay, which eventually became the home of Mrs Cox and her children.” To Ruddick, this is “random and without meaning.” So of the characters in the book 2 of the 3 men Florence sleeps with are from Jamaica, as well as her housekeeper, commonly seen as a linchpin in the murder. It is incredible that Ruddick at no point discusses the sexual politics of colonialism, the structure and function of colonialist violence as it impacts the bodies of those who are its subjects. And how partaking in colonialism in a colony might affect, change, or determine the mindset of the colonizer as well. To offer that short little paragraph as a summary of funny “coincidences” is incredible.

I don’t think it matters, ultimately, who pulled the trigger, so to say (there’s also a suicide theory, which, if I understand the internet correctly, Ruddick represents very badly and incompletely) – the book, which prides itself on offering a lot of contexts, given the paucity of information available, subtracts from the story the most relevant questions. The way Charles Bravo uses impregnation through rape as a weapon to acquire the fortune of the rich widow Florence is impossible to examine without recourse to the context of his origins in Jamaica. His reaction to the other man in Florence’s life is empty without connection to their shared beginnings in colonialist exploitation in the West Indies. And the role of Jane Cox has to be analyzed in connection with her roots and understanding of the sexual politics of colonialism. A book that has a curiously apropos connection to A Death in the Priory is Jean Rhys’ rewriting of Jane Eyre in Wide Sargasso Sea. Rhys gives us a white immigrant from Jamaica, daughter of impoverished former planters, who is driven to madness by her English husband. The psychology of Antoinette, her situation with regard to class and race, as well as her connection to Grace Poole all offer examples of a complex conversation the ingredients of which are right there in the Charles Bravo murder case.

None of this is offered by Ruddick, who, instead, includes a photo of “the author search[ing] for Cox’s descendants in the West Indies.” His bias is enormous and almost offensively obvious, but because it is so obvious, it does not entirely erase the accomplishments of the book as outlined earlier. He doesn’t obfuscate or hide these biases, and, as with many other books, you just have to do some additional work of your own to level and contextualize his theories. There are many problems with this book, but within the broader context of historical True Crime as a genre, most of which is bad, gullible trash, this is quite decent for what it is. If you don’t know the case, it’s a good read – and a good jumping off point for more reading.