So you have seen me announce my TDDL coverage – and then nothing happened? Apologies, did NOT have a good week. Anyway, today the awards are voted on by the jurors, and I thought that’s a solid opportunity to summarize the past 3 days of readings for you.

So you have seen me announce my TDDL coverage – and then nothing happened? Apologies, did NOT have a good week. Anyway, today the awards are voted on by the jurors, and I thought that’s a solid opportunity to summarize the past 3 days of readings for you.

And boy did we have some readings. There were no truly excellent texts on the first day, balanced out by some odd walks on the Caucasian side, and then there were two to three spectacular readings on the second day, and a solid third day. I’m not going to go through them chronologically, so as not to needlessly repeat myself. Writing about everything at once allows me to be slightly less vitriolic than I usually am – seeing the arc of a year’s crop of invitations is intriguing.

One of the most significant developments was the dialogue that the texts had with Sharon Dodua Otoo’s speech that introduced the events. Otoo’s speech very calmly discussed the role of race in German literature – she spoke clearly and eloquently about solidarity, lived experience, about the room to write yourself in a white society when you’re Black, when you’re Othered, by readers, publishers, other authors. What does representation mean to Black artists? The most urgent question, regarding this year’s competition, surfaces early in the speech: do some white writers write the way they do because they imagine their readership exclusively white? What are the expectations regarding literary “speech” – Otoo cites Chinua Achebe, who declared that “writers are not only writers, they are also citizens.”

And so to these three days of readings, with one (1) writer with Egyptian roots and one (1) writer with Kosovan roots, and everybody else with less complex backgrounds. How did these writers rise to the challenge of being “not only writers, [but] also citizens?” Poorly, for the most part.

I’m splitting the post into the writers I did not like, on the one hand, and a second post about my favorites, and then a third about the actual results.

My favorites are, in this order:

Helga Schubert

Laura Freudenthaler

Egon Christian Leitner

Lydia Haider

Audience Award: Hanna Herbst

This post, however, is about the others.

Let’s begin with the interesting, inoffensive, but banal – Meral Kureyshi and Jasmin Ramadan offered light texts that were written with skill and invested with some intriguing energy, but fell flat, ultimately. Both concerned with questions of gender, they differed in tone – Kureyshi read us a soft, pensive monologue about a woman’s love life. There isn’t one bad sentence in the whole story, on the contrary, it contains several striking observations and comments, but it lacks, ultimately, something to draw the reader through it. The opposite is true for Jasmin Ramadan. Author of several novels, her story is punchy – a sharp look at modern gender dynamics, written in a light, quick style, which, for this kind of award and environment, was a bit too light. Acknowledging the difficulties of calling something “literary” without qualifying the precariousness of that judgment, this text still fell short of what is considered literary, at least in this context. And there are certainly questions here, questions I would have liked the judges to ask, about representation of female writing, and of writers of color, and what the limits of our idea of literary writing mean for this kind of writer, particularly because Ramadan consistently works with the most fascinating notions of representation in her literary work. Hers was the first text, and a fantastic opportunity to tie a discussion of the text into the Rede zur Literatur, which supposedly frames the whole week. Spoiler alert: the judges did not refer back to Otoo’s speech a single time. Not that first day, nor any day thereafter. Not surprised, but still disappointed. It feels off, slotting Kureyshi and Ramadan somewhere into the middle of the field, but it is what it is.

Similarly in the middle, but for entirely different reasons, is another pair of writers, Jörg Piringer and Levin Westermann. Every year, there’s at least one poet – and it is remarkably often that poet who wins an award. Nora Gomringer won the main award, for example. Poets writing prose can be exciting. Unexpectedly, this year, we were offered poets writing poetry. And not just text that is written in short lines. In their readings, both Piringer and Westermann emphasized the structural qualities of poetry. Jörg Piringer offered a history of our current reality, connected to a metaphor from martial arts. He worked in free rhythms, but scrupulously emphasized the ends of lines, forming the poem as much orally as he did on the page. The reading was more rhythmic than the writing – a veteran of the digital poetry scene, indeed, often considered a pioneer, Piringer’s reading was impressively sharp, powerful enough to make readers read past many of the less than sharp observations of history and the present. The martial arts metaphor sits uncomfortably in the middle of a text which does not in any way reflect on the patriarchal nature of historiography, written for an implied audience that does not particularly need that kind of reflection: white, tech-savvy men. The masculine obsession with martial arts fits this pattern too well, not to mention the pronounced performance of the whole text. Still, until I reread Lydia Haider’s remarkable text quietly tonight, I considered Piringer’s poem one of the four best texts of the competition. I was never in danger of considering Levin Westermann’s text one of those. Westermann is an accomplished, widely published poet – and in his text, he shows himself to also be widely read. An early quote from a Matthew Zapruder poem cannot but make us think of Zapruder’s recent, mildly controversial book Why Poetry, a defense of poetry, which may as well serve as an explanation of why Westermann offered up this text. Other writers cited in the text include Rilke, Dillard and Jorie Graham. The text itself consists of rhythmic but irregularly metered and highly irregularly rhymed lines, making strong use of repetition and other kinds of form to produce a formally dense text, which has next to nothing to say that cannot be found in Zapruder’s text. The occasional political notes struck are bland, and drown in the incessant formal games that Westermann, unlike some late Graham, never convincingly connects to something that matters. The effect is strangely masturbatory, a display (sound, fury etc.).

Speaking of masturbatory – male writers tend to come to Klagenfurt with texts celebrating, well, themselves, in one way or another, and it’s never the stylistically brilliant ones either. Last year, an award was handed out to a navel-gazing story of a writer writing about his day walking through his city, picking up groceries (details may vary), having a series of extremely minor epiphanies, presented in the flattest prose imaginable. And the streak continues, unabated, with the next pair. Leonard Hieronymi and Matthias Senkel offered badly written stories that were largely pointless literary exercises with the sole purpose of centering the writers in question, though, superficially, their stories appear to be different. Matthias Senkel presented a story about a mystery, about an archaeological dig, written like a mosaic, composed of sections set in different periods. It tries to use scientific vocabulary to make the story discursively complex, with notes of Richard Powers and similar writers, but he entirely lacks a broader view or any sense of style. His is not the worst written story of the competition, but it’s also not too far off. His goal is one of faking layers of complexity to catfish readers into overlooking the blandness of the actual writing on the page. Some of the dialogue is downright risible, the information in the story closer to wiki-sourced infodumps than to well-digested and productively used knowledge, and the various attempts to play or toy with the reader a transparent ploy to engage in dialogue with a very specific (white, male) readership, which is curiously popular in German literature, as attested to by the popularity of the Barons of Blandness Thomas Glavinic and Georg Klein, both of whom have made a career of papering over poor writing with various kinds of metafictional games, in the case of Glavinic with some additional limp masculinity. Speaking of which: Leonard Hieronymi entered a story into the competition that read like a carbon copy of the travel stories written by Christian Kracht and friends in the earlyy and mid-1990s. It’s almost not worth discussing. Hieronymi, member of a group called “The Rich Kids of Literature” (it’s an English-language title, because of course it is), writes about getting horribly drunk, then taking a trip to the Romanian city of Constanta by the Black Sea, meeting famed Romanian poet Mircea Dinescu. There, he evokes Ovid and his exile, which he wrote about in the beautiful Tristia. In between all this he offers observations of Romania that switch between the banal and the offensive, and in the end he returns, having learned nothing. The expectations inscribed in books like this, the sense of who writes, who reads and who gets written about is stark, but at least, let me say that, Hieronymi comes close to making his politics explicit.

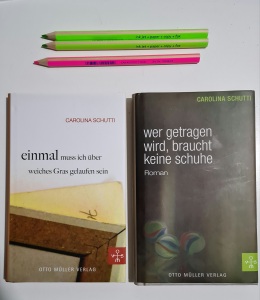

That’s not true for the next group of writers, Katja Schönherr, Lisa Krusche and Carolina Schutti. Let me start with Schutti, because I have very little to say about her story that I hadn’t said about her novels before. To quote my pre-Bachmann review:

Carolina Schutti has a tonal consistency that is admirable, if maddening. In her very first book she zeroes in on a style that seems derivative, but really isn’t epigonal in any typical sense. She doesn’t echo specific writers as much as a general tone. As a concert pianist she has said in an interview that she always writes for listeners as well – and indeed, from the first line you can hear the voice in these books. And you know, eerily, what this voice is? It’s the typical note struck by the average reader at the Bachmannpreis – this measured pronunciation that situates texts right between light and somber, investing pauses and turns with meaning that they don’t have on the page.

And

these books are… specific cultural performances, with a specific audience in mind. Schutti, from page one, line one of her first novel, immediately seizes on a tone and style and never abandons it. Open any page at random, and you can hear it spoken slowly into a microphone in Klagenfurt. And honestly, they probably make for great analyses by scholars and judges, just not for particularly good literature. The expectation behind this style is what’s truly remarkable – it’s an inherent expectation of importance, an arrogance of whiteness that is at times breathtaking.

I also note the sense of exploitation of marginality. All of this is exactly true for the story she presented. Tone, style, exploitation, all there. Again, someone on the margins, again, someone struggling with language. And like other Bachmann-writers in previous years, for example Stephan Lohse, she doesn’t shy away from indirectly using Blackness as a way to feed and expand her already dubious narratives of marginality. Her protagonist, in a moment of crisis, sees a documentary about Africa on TV, exclaiming “Ich bin in Afrika.” Schutti’s text is a paint-by-numbers Klagenfurt text, in the worst way. Her books sound like they should be read at TDDL, so did her story, which she read exactly this way, and she uses the same tropes of marginality to elevate her text into a borrowed relevancy. At least, one is tempted to say, Katja Schönherr’s protagonist isn’t marginalized. Just a regular white female character. But Schönherr also, almost aggressively, makes it clear that she has a very specific implicit audience. I’ll admit, it’s bad luck that her story came out when we are all so much more aware of the necessity of elevating marginalized voices, when people march to protest the disregard for Black and trans lives. Let me tell you what Schönherr’s story is about in the least judgy vocabulary: a (white) woman goes to the Zoo with husband and daughter, struggling with her life, worried she might die (she’s not ill). She sees an orangutan who picks up a sign (we are never told which) and holds it up. A conversation between various onlookers ensues, as they debate whether the apparent demonstration by the ape is right-, or leftwing, or neutral. Complaints arise that the demonstration isn’t narrowly tailored to ape-relevant concerns, and the protagonist slowly comes around to feeling solidarity with the orangutan, who, she feels, should be allowed to have its say. After the sign is abandoned, she acquires orangutan costumes and goes to the zoo with her daughter, costume-clad, with the sign, to continue the protest, until she gets kicked out. To cite Otoo, as the judges have conspicuously not done: who is this for? Who is this about? Who is included, who is not? If every writer is a citizen, and if we are to look at who the writer’s empathy is for, how do we read texts like Schönherr’s? Using the figure of public protest merely as a mirror for a white woman’s ennui and an a fear of death is deeply strange and unpleasant – and shows a profound disengagement with the reasons for such public protests, not to mention other…issues with the story. Similar problems of disengagement are displayed in the text by Lisa Krusche. Of the three in this final group, it is by far the most well written. I admit, I had to read it multiple times to engage with the tone and the writing, but there you are. That said, her story about disaffected youth, a sense of connection with an environment that in Krusche’s pen turns even the inorganic organic, and virtual spaces suffers from the exact same problem as Schönherr’s story. The same questions apply – though she masks it better than Schönherr’s plain offering. The central theoretical text for Krusche’s story is Donna Haraway’s late-career book Staying with the Trouble, in which Haraway completes a disengagement with real, tangible change, with a connection to intersectional feminist issues, in favor of a loose examination of kinship and inter-species solidarity that was a long time coming in her work. This excellent essay by Sophie Lewis explains in detail where the problems with Haraway’s book are. Krusche’s story would have been tonally off in any year of the competition, but it sounds a particularly discordant tone this year, particularly. It’s not just that the police as an institution is noted and dismissed as “maybe inherently humorous,” which, I have no words. The use of virtual spaces in narratives is especially fraught. There are copious essays noting why texts like Ready Player Go are structurally racist, and what the imagination of whiteness in virtual spaces really means. Afrofuturism has offered much pushback to these imagined spaces, and clarified why there are no real neutral visions of the future. Krusche does not engage any of these questions and offers, at the end, a general pessimism, a view of revolution that is colorblind in the worst way. It’s an unpleasant text, masked by a sometimes stunningly beautiful sense of reality, borrowed straight from JG Ballard’s unpleasant dystopias of white distress. Sophie Lewis makes it abundantly clear that Haraway’s avoidance of empathetic solutions to patriarchal and racist violence (in fact, she specifically reproduces racism in the book) isn’t a byproduct, but an essential structural component of elevating oddkins and “kinnovations” over families and the masses of humans. The same is true, though less focused, of Lisa Krusche’s text. To connect the text to Sharon Otoo’s speech: who is its audience? Who do we have empathy for? Krusche’s text is about whiteness in multiple problematic ways. Nam Le, in his sticky book-length essay on David Malouf, notes the role of the bush, the untamed wilderness, in the imagination of colonial settler writing. He writes that for immigrants, “whiteness is our bush” – for Lisa Krusche, the old oppositions are active. The bush is still the bush, dystopian, wild, decaying. The contrast even to writers like Vandermeer, with all his flaws, is instructive. A text inspired by a past that we should be learning to read critically instead.

More on the writers I wanted to win in the next post.

That makes it a bit of a disappointment that her next novel, Available Dark, does not rise to the same heights. We appear to meet another art obsessive, we appear to be drawn into another maze of the arduous space between art and life, as Cass Neary is flown to Helsinki to help assess the value of a set of photographs. Instead, in this book, photography and the art and technique of it is incidental. Available Dark sidles up even closer to noir conventions, with Neary sometimes merely following the winds that blow her across the icy Scandinavian plains of a baroque plot. As the resolution presents itself I was more irritated than anything. A lot of stupid people doing stupid things and killing other people for even more generic, stupid reasons. I know that a lot of crime novels are centered around the stupid things that stupid people do (and the half-clever ways they try to cover it up), but that’s not what I find interesting. There’s a disturbing thing that happens at the end of Generation Loss that I am unwilling to spoil, but it is entirely in line with that book’s general theme, but it expands it, and opens up Cass Neary’s world into another direction – it’s tough to see it fall by the wayside within the first couple of pages of Available Dark, serving merely as motivation for Cass to take that Helsinki job. However, whatever misgivings I may have about Available Dark, they don’t tarnish Generation Loss, which is fantastic. Read it if you like that sort of thing. It’s good.

That makes it a bit of a disappointment that her next novel, Available Dark, does not rise to the same heights. We appear to meet another art obsessive, we appear to be drawn into another maze of the arduous space between art and life, as Cass Neary is flown to Helsinki to help assess the value of a set of photographs. Instead, in this book, photography and the art and technique of it is incidental. Available Dark sidles up even closer to noir conventions, with Neary sometimes merely following the winds that blow her across the icy Scandinavian plains of a baroque plot. As the resolution presents itself I was more irritated than anything. A lot of stupid people doing stupid things and killing other people for even more generic, stupid reasons. I know that a lot of crime novels are centered around the stupid things that stupid people do (and the half-clever ways they try to cover it up), but that’s not what I find interesting. There’s a disturbing thing that happens at the end of Generation Loss that I am unwilling to spoil, but it is entirely in line with that book’s general theme, but it expands it, and opens up Cass Neary’s world into another direction – it’s tough to see it fall by the wayside within the first couple of pages of Available Dark, serving merely as motivation for Cass to take that Helsinki job. However, whatever misgivings I may have about Available Dark, they don’t tarnish Generation Loss, which is fantastic. Read it if you like that sort of thing. It’s good.

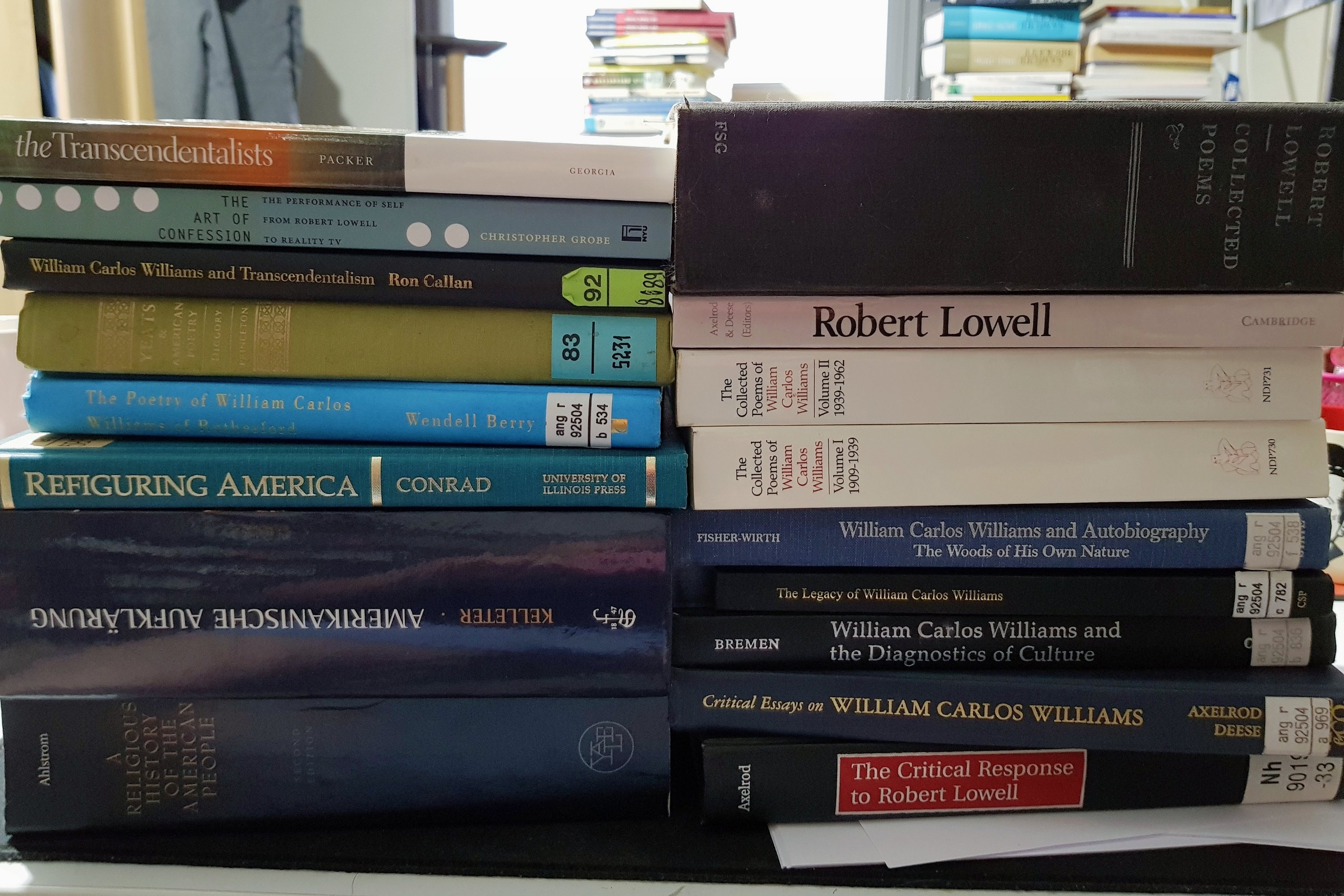

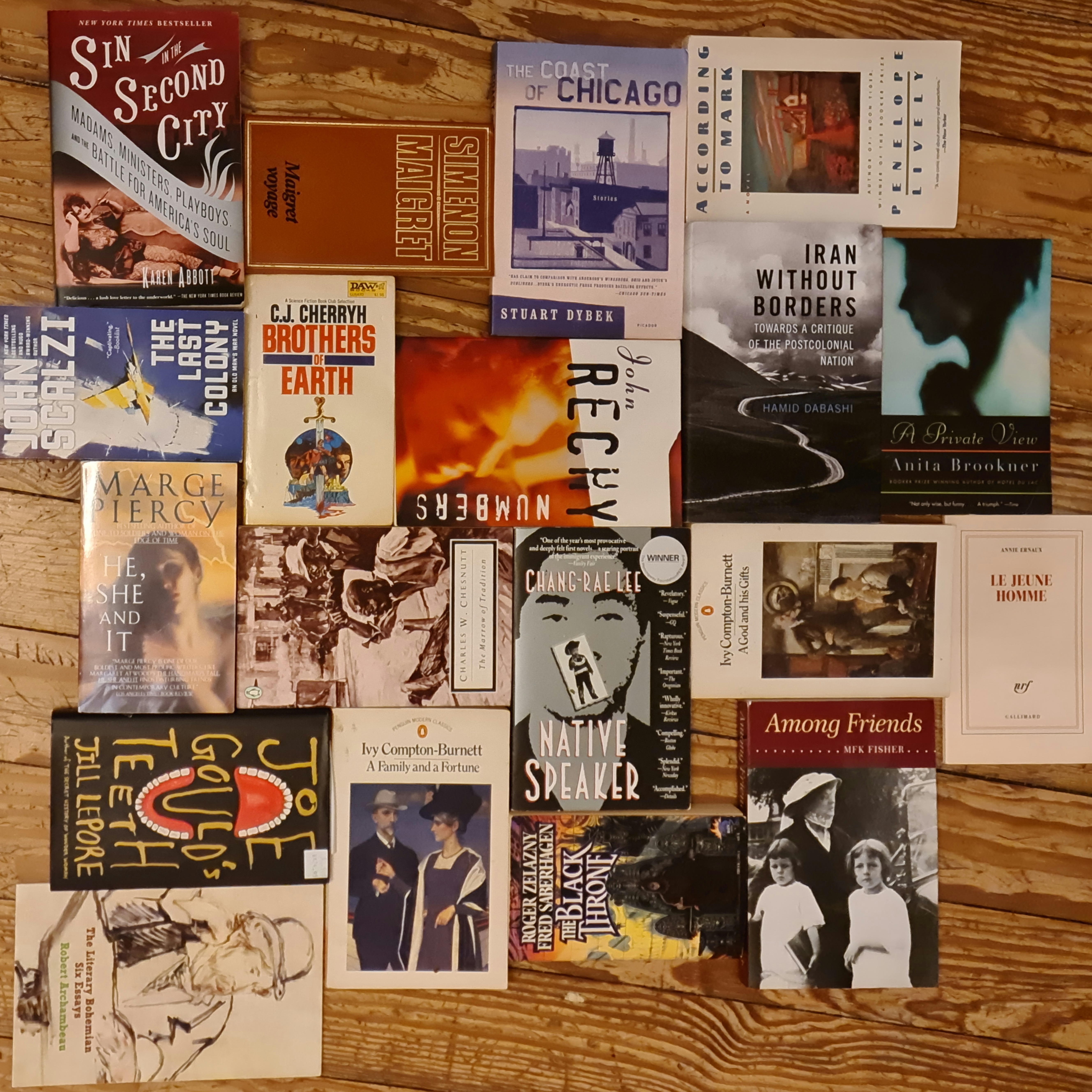

So I have a lot of books in this apartment of mine,

So I have a lot of books in this apartment of mine,

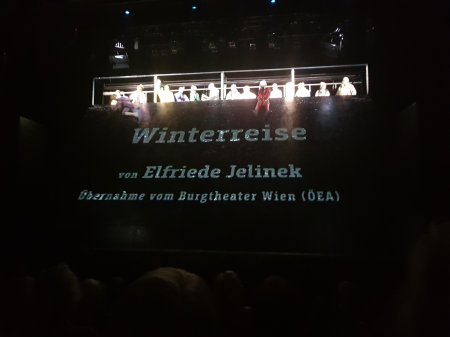

So I complain about translation a lot here, and if you’re following this blog, I’m sure you’re a little bit tired of it, but among the whining about infidelity, and cheating the reader etc. there is another effect that is a bit underrated. Jakob Nolte’s subpar but interesting sophomore novel Schreckliche Gewalten is a good example of that. Here’s the thing: I love Thomas Pynchon’s work to a frankly upsetting degree, but his work suffers from the same problem that other Americans also have in German translation. It’s depth of style. Somehow, in the 1960s, German translators decided that in order to give German audiences a real feeling of “Americanness” in style, there had to be a certain ease of style too, a certain “Americanness,” if you will. Which leads to some writers like Saul Bellow or Philip Roth to read much less stylistically complex than they do in English. I’m not here to debate the literary value of Bellow or Roth, but, missteps aside, it’s inarguable that they were, on a sentence by sentence level, quite excellent prose writers. They don’t read like that in German, on a sentence by sentence level. And postmodern writers like Barth and Pynchon fared even worse. Pynchon can be quite a knotty writer of prose, and for a long time, translations did not reflect the complexities of his style. But generation on generation of writers grew up on his books in translation. Gravity’s Rainbow, for example, was translated by none other than Elfriede Jelinek – Pynchon’s books had the imprimatur of literary royalty, whatever the details of style. But if you are a young man whose literary proclivities lead him down the path of postmodernity, there’s a chance you won’t just have structural debts to the writers that inspired you – you’ll also have stylistic debts. And while Jakob Nolte is clearly a well read author who very clearly has a solid command of English, the most striking thought I had while reading his novel was – how it read like a poor man’s Pynchon in terms of structure, but nothing in any way like Pynchon in terms of style – and honestly, I think I blame translation for this.

So I complain about translation a lot here, and if you’re following this blog, I’m sure you’re a little bit tired of it, but among the whining about infidelity, and cheating the reader etc. there is another effect that is a bit underrated. Jakob Nolte’s subpar but interesting sophomore novel Schreckliche Gewalten is a good example of that. Here’s the thing: I love Thomas Pynchon’s work to a frankly upsetting degree, but his work suffers from the same problem that other Americans also have in German translation. It’s depth of style. Somehow, in the 1960s, German translators decided that in order to give German audiences a real feeling of “Americanness” in style, there had to be a certain ease of style too, a certain “Americanness,” if you will. Which leads to some writers like Saul Bellow or Philip Roth to read much less stylistically complex than they do in English. I’m not here to debate the literary value of Bellow or Roth, but, missteps aside, it’s inarguable that they were, on a sentence by sentence level, quite excellent prose writers. They don’t read like that in German, on a sentence by sentence level. And postmodern writers like Barth and Pynchon fared even worse. Pynchon can be quite a knotty writer of prose, and for a long time, translations did not reflect the complexities of his style. But generation on generation of writers grew up on his books in translation. Gravity’s Rainbow, for example, was translated by none other than Elfriede Jelinek – Pynchon’s books had the imprimatur of literary royalty, whatever the details of style. But if you are a young man whose literary proclivities lead him down the path of postmodernity, there’s a chance you won’t just have structural debts to the writers that inspired you – you’ll also have stylistic debts. And while Jakob Nolte is clearly a well read author who very clearly has a solid command of English, the most striking thought I had while reading his novel was – how it read like a poor man’s Pynchon in terms of structure, but nothing in any way like Pynchon in terms of style – and honestly, I think I blame translation for this.

hings are coming to an end. Day Three closed the active portion of the Bachmannpreis with a thoroughly interesting set of texts. Tomorrow prizes will be awarded. At least one of today’s writers should win one, as we have seen the best text of the competition (as well as one of the worst) but we’ll get to that. Meanwhile, here is

hings are coming to an end. Day Three closed the active portion of the Bachmannpreis with a thoroughly interesting set of texts. Tomorrow prizes will be awarded. At least one of today’s writers should win one, as we have seen the best text of the competition (as well as one of the worst) but we’ll get to that. Meanwhile, here is