Millar, Mark; JG Jones, Paul Mounts (2008), Wanted, Top Cow

ISBN 9781582404974

Millar, Mark; John Romita Jr. et al. (2010), Kick-Ass, Titan Books

ISBN 9781848565357

This isn’t the first time, nor will it be the last, that I confess my admiration for Mark Millar’s work. I consider Millar’s books to be among the best published in comics these days, although at least half that admiration is owed to his artists. His comics have pencils by major artists as J.G. Jones (Wanted), Brian Hitch (The Ultimates) and John Romita Jr. (Kick-Ass). I try to read as much of his work as possible, even when, as in Ultimate X-Men, it appears to be slightly sub-par. In books like Kick-Ass or Wanted, it isn’t. Mark Millar is known to publicly overemphasize his importance and brilliance, but sometimes, his material just works perfectly. On the other hand, Millar keeps bothering me in different ways. In comics, the fact that every character and action comes with its visual representation, the fact, too, that you can’t bury essentials in pages of text, can create problematic depictions of various issues. Many comics touch upon some of these issues,, and Millar is no exception. However, while a lightweight series like Y: The Last Man provides a quietly reactionary soap opera, Mark Millar, clearly enjoying his role as provocative writer, dishes up a densely narrated drama in his books, where all the elements are so well posited and constructed that they heighten the importance of each individual element, including the troubling ones. The Ultimates, for example, is a clever and sparsely told disquisition about military power and its relationship to basic elements of culture, from the treatment of women, to chauvinism, racism and much more. Every character, every line, every panel in the comic seems to be designed to work that angle. The Ultimates is almost flawlessly executed.

This isn’t the first time, nor will it be the last, that I confess my admiration for Mark Millar’s work. I consider Millar’s books to be among the best published in comics these days, although at least half that admiration is owed to his artists. His comics have pencils by major artists as J.G. Jones (Wanted), Brian Hitch (The Ultimates) and John Romita Jr. (Kick-Ass). I try to read as much of his work as possible, even when, as in Ultimate X-Men, it appears to be slightly sub-par. In books like Kick-Ass or Wanted, it isn’t. Mark Millar is known to publicly overemphasize his importance and brilliance, but sometimes, his material just works perfectly. On the other hand, Millar keeps bothering me in different ways. In comics, the fact that every character and action comes with its visual representation, the fact, too, that you can’t bury essentials in pages of text, can create problematic depictions of various issues. Many comics touch upon some of these issues,, and Millar is no exception. However, while a lightweight series like Y: The Last Man provides a quietly reactionary soap opera, Mark Millar, clearly enjoying his role as provocative writer, dishes up a densely narrated drama in his books, where all the elements are so well posited and constructed that they heighten the importance of each individual element, including the troubling ones. The Ultimates, for example, is a clever and sparsely told disquisition about military power and its relationship to basic elements of culture, from the treatment of women, to chauvinism, racism and much more. Every character, every line, every panel in the comic seems to be designed to work that angle. The Ultimates is almost flawlessly executed.

Both great writers like Grant Morrison and bad ones like Jeph Loeb tend to use the serial nature of mainstream comics to write expansive, associative work. There’s a line threaded through a series of books like Morrison’s fantastic run on the New X-Men, but images and characters tend to touch on many issues and moods. In comparison, Millar is uncommonly obsessed with the same topics and ideas within one book or one run. Although Millar’s run on the Ultimate X-Men pales beside Morrison’s work with more or less the same characters (more in a few weeks on this blog), it’s still strong, and most of all: it’s a taut, concentrated genre exercise. Millar reconstructs the X-Men from the bottom up, he re-introduces them and their themes for a new audience; in their case it makes for a certain dullness, because we know the X-Men by now, we’re familiar with their themes. Additionally, his X-Men work was largely penciled by Adam Kubert, who, despite his fame, is clearly not a very good fit. Millar, as the X-Men stories, or, to an extent, his work with the Fantastic Four has shown, is a writer with a limited palette. He’s excellent in what he does best, but remove a few of the variables, or change them, and his work can quickly seem dull and uninteresting. But if the artist, the material and the setting is right, as in the aforementioned Ultimates, his writing is incredible: it’s hard to deny the perfection of The Ultimates. On the other hand, two of his more original graphic novels, Wanted and Kick-Ass, seem very divisive. In my opinion, both of these books compare well to the best ‘regular’ literature I’ve read this year, but their highly violent content has not gone over very well with all their readers.

Both great writers like Grant Morrison and bad ones like Jeph Loeb tend to use the serial nature of mainstream comics to write expansive, associative work. There’s a line threaded through a series of books like Morrison’s fantastic run on the New X-Men, but images and characters tend to touch on many issues and moods. In comparison, Millar is uncommonly obsessed with the same topics and ideas within one book or one run. Although Millar’s run on the Ultimate X-Men pales beside Morrison’s work with more or less the same characters (more in a few weeks on this blog), it’s still strong, and most of all: it’s a taut, concentrated genre exercise. Millar reconstructs the X-Men from the bottom up, he re-introduces them and their themes for a new audience; in their case it makes for a certain dullness, because we know the X-Men by now, we’re familiar with their themes. Additionally, his X-Men work was largely penciled by Adam Kubert, who, despite his fame, is clearly not a very good fit. Millar, as the X-Men stories, or, to an extent, his work with the Fantastic Four has shown, is a writer with a limited palette. He’s excellent in what he does best, but remove a few of the variables, or change them, and his work can quickly seem dull and uninteresting. But if the artist, the material and the setting is right, as in the aforementioned Ultimates, his writing is incredible: it’s hard to deny the perfection of The Ultimates. On the other hand, two of his more original graphic novels, Wanted and Kick-Ass, seem very divisive. In my opinion, both of these books compare well to the best ‘regular’ literature I’ve read this year, but their highly violent content has not gone over very well with all their readers.

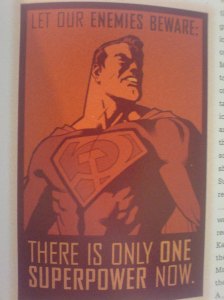

Kick-Ass is especially violent, both in terms of actual, depicted violence, and in terms of emotional violence. It’s a borderline-surreal tale that seems to be premised on the idea of what super heroes would look like ‘in the real world’, but, as any closer look will immediately reveal, is anything but that kind of book. Kick-Ass and Wanted are books soaked with decades of superhero (or supervillain) history. Not just the history that surfaces in explicit and implicit references to canonical works, but the whole idea of superhero comics, their iconic and intellectual function in our cultures. Not even Morrison is so obsessed with the minutiae of comics and comics references alone. Millar’s books seem to have soaked up heaps and heaps of comics and internalized them, and seem to develop their ideas further and further. Millar’s work on The Authority is similar to The Ultimates, grappling with similar themes, but it lacks the incredible polish and concentration of the later work. Plot-lines and concepts seem to complete or prolong questions raised in the earlier work. In the same way, Kick-Ass, while not a regular superhero comic, is a continuation of an earlier Millar book, and is best read in that context, I think. That earlier book is Wanted, published in 6 issues between 2003 and 2004. Wanted is the story of Wesley Gibson, a frustrated young white man, who finds out his father was an extremely talented killer and takes up with a gang of super-villains. Given that the main character is a super-villain-in-waiting, its not surprising that the comic deals with hate a lot. The narrator is the protagonist, who, in the fourth panel, complains that he’s “taking shit from my African American boss”.

Kick-Ass is especially violent, both in terms of actual, depicted violence, and in terms of emotional violence. It’s a borderline-surreal tale that seems to be premised on the idea of what super heroes would look like ‘in the real world’, but, as any closer look will immediately reveal, is anything but that kind of book. Kick-Ass and Wanted are books soaked with decades of superhero (or supervillain) history. Not just the history that surfaces in explicit and implicit references to canonical works, but the whole idea of superhero comics, their iconic and intellectual function in our cultures. Not even Morrison is so obsessed with the minutiae of comics and comics references alone. Millar’s books seem to have soaked up heaps and heaps of comics and internalized them, and seem to develop their ideas further and further. Millar’s work on The Authority is similar to The Ultimates, grappling with similar themes, but it lacks the incredible polish and concentration of the later work. Plot-lines and concepts seem to complete or prolong questions raised in the earlier work. In the same way, Kick-Ass, while not a regular superhero comic, is a continuation of an earlier Millar book, and is best read in that context, I think. That earlier book is Wanted, published in 6 issues between 2003 and 2004. Wanted is the story of Wesley Gibson, a frustrated young white man, who finds out his father was an extremely talented killer and takes up with a gang of super-villains. Given that the main character is a super-villain-in-waiting, its not surprising that the comic deals with hate a lot. The narrator is the protagonist, who, in the fourth panel, complains that he’s “taking shit from my African American boss”.

The word “boss” is helpfully printed in bold to point out Wesley’s incredulity at having to take flak from someone who is not as nicely white as he is. This line of thinking continues throughout the comic, which glories in mass shootings, rape and other distasteful actions. Apart from calling him a villain, the book never once breaks through that mood, effectively providing an appraising account of one of the least likable characters in fiction. At the end of the book, Wesley turns even on the readers of the comic, accusing them of weakness. The penultimate panel has, however, a striking image. While telling us that we’re “going to close this book and buy something else to fill that big, empty hole [they]’ve created in [our] life”, we see the hand of a customer buying a couple of comics. One of them is an issue of Wanted. I’d argue that that image short-circuits the book, inviting us to read it in terms of comics and iconicity. J.G. Jones’ clear and highly detailed art creates an extremely realistic world that houses an fantastical story. The contrast between the narrative, characters, the voices, and the visual representation of them turns a ratio upside down that tends to dominate graphic novels. If we take, for instance, Vaughan and Guerra’s Y: The Last Man, we find a regular Science Fiction story, clearly intent upon finding out “what would really happen” if all men died, and “what really could have caused it”. Vaughan, as in much else of his work, strains to find a believable voice, and dialogue that sounds “real”.

The word “boss” is helpfully printed in bold to point out Wesley’s incredulity at having to take flak from someone who is not as nicely white as he is. This line of thinking continues throughout the comic, which glories in mass shootings, rape and other distasteful actions. Apart from calling him a villain, the book never once breaks through that mood, effectively providing an appraising account of one of the least likable characters in fiction. At the end of the book, Wesley turns even on the readers of the comic, accusing them of weakness. The penultimate panel has, however, a striking image. While telling us that we’re “going to close this book and buy something else to fill that big, empty hole [they]’ve created in [our] life”, we see the hand of a customer buying a couple of comics. One of them is an issue of Wanted. I’d argue that that image short-circuits the book, inviting us to read it in terms of comics and iconicity. J.G. Jones’ clear and highly detailed art creates an extremely realistic world that houses an fantastical story. The contrast between the narrative, characters, the voices, and the visual representation of them turns a ratio upside down that tends to dominate graphic novels. If we take, for instance, Vaughan and Guerra’s Y: The Last Man, we find a regular Science Fiction story, clearly intent upon finding out “what would really happen” if all men died, and “what really could have caused it”. Vaughan, as in much else of his work, strains to find a believable voice, and dialogue that sounds “real”.

Pia Guerra’s pencils, in contrast, while depicting a realistic setting, indulge in iconicity. Every depiction of humans is extremely idealized and refers not to a sketch of an actual person (however they were actually created) but to a culturally developed idea of a shape. The female form, the depiction of pregnant women, of militant women, of black women, all the details of the eponymous man: this is superhero comics material, just without the spandex. JG Jones’ far more sophisticated work aims for more realism while reflecting a discussion of issues of iconicity in countless details of the depiction of the characters. Jones’ art is so detailed it slows the story down, scattering it into a series of tableaux. There is a tension between the superhero aspects, like the glossy poses that many of the uber-cool villains assume, or the odd, surreal accessoires they wear, and the wrinkly realism of the artwork itself. The results are intriguing, and absolutely stunning. While none of this is Millar’s art, he did write the content for Jones to fill in, and the very choice of Jones (who is, after all, famous for his style, cf. Greg Rucka’s Wonder Woman run) as artist was inspired. In a book like Wanted, which, as I pointed out, thrives off the kind of tensions that mark J.G. Jones work, nothing seems off. Everything here fits like a glove. The problem with this is, from a reader’s perspective, that it naturally reinforces any troubling issues raised in Millar’s script. However, Wesley is such an exuberantly bigoted character that the book makes more sense in a reading that assumes it to be a satire, than a reading that takes the opinions and ideology of its characters at face values. It’s a satire, and a sharp-tongued one at that, drawing on more than just media criticism. In a time-honored comics tradition, from the Skrulls to Morrison’s and Moore’s masterpieces, it questions conventional narratives and perceptions.

There is still more to it, though. The criticism it contains isn’t really new or spectacular, following lines established by the comics I mentioned and movies such as Natural Born Killers. Millar’s dense and focused way of telling and constructing his story is fairly rare, however. Additionally, at least for me, it’s hard now to disregard Kick-Ass when reading and commenting upon Wanted, which is much enhanced when assuming that it is part of a narrative or intellectual trajectory that includes Kick-Ass. On a surface level, the two books couldn’t be more different. Kick-Ass‘ art is almost the exact opposite of Jones’. While Jones did both pencils and inks in Wanted, John Romita Jr. only did the pencils in Kick-Ass. Its inks are handled by Tom Palmer, and one feels an odd disconnect here. This is worth noting, since Palmer is one of the most legendary inkers in the business today. His inks in Byrne’s X-Men run (although I’m not partial to Byrne’s pencils) are nothing short of stunning, for example, and his influence in the industry is hard to overestimate. But in Kick-Ass, his work and Romita Jr.’s are a bad fit. The point is that J.G .Jones’ art is of a piece and hits you straight in the face. It overwhelms you, lets you examine the world of Wanted in full dark detail. None of that here. It’s not just the inks, however. Romita Jr.’s art is low on details, and the few panels that contain many can seem almost sloppily done. In Romita Jr.’s art, objects and people merge, and objects in different states of matter (liquids, gases, solids) start to resemble one another. The effect is both disconcerting and cartoonish. So, on the level of the art, you have a focused, detailed, fully coherent book, and a book where the different elements don’t quite fit, where the art in general is always slightly out of focus. But the connection is, of course Millar. The two novels’ art is similar in the sense of perfectly fitting the writing. The changes in the art correspond directly to the changes in the narrative.

There is still more to it, though. The criticism it contains isn’t really new or spectacular, following lines established by the comics I mentioned and movies such as Natural Born Killers. Millar’s dense and focused way of telling and constructing his story is fairly rare, however. Additionally, at least for me, it’s hard now to disregard Kick-Ass when reading and commenting upon Wanted, which is much enhanced when assuming that it is part of a narrative or intellectual trajectory that includes Kick-Ass. On a surface level, the two books couldn’t be more different. Kick-Ass‘ art is almost the exact opposite of Jones’. While Jones did both pencils and inks in Wanted, John Romita Jr. only did the pencils in Kick-Ass. Its inks are handled by Tom Palmer, and one feels an odd disconnect here. This is worth noting, since Palmer is one of the most legendary inkers in the business today. His inks in Byrne’s X-Men run (although I’m not partial to Byrne’s pencils) are nothing short of stunning, for example, and his influence in the industry is hard to overestimate. But in Kick-Ass, his work and Romita Jr.’s are a bad fit. The point is that J.G .Jones’ art is of a piece and hits you straight in the face. It overwhelms you, lets you examine the world of Wanted in full dark detail. None of that here. It’s not just the inks, however. Romita Jr.’s art is low on details, and the few panels that contain many can seem almost sloppily done. In Romita Jr.’s art, objects and people merge, and objects in different states of matter (liquids, gases, solids) start to resemble one another. The effect is both disconcerting and cartoonish. So, on the level of the art, you have a focused, detailed, fully coherent book, and a book where the different elements don’t quite fit, where the art in general is always slightly out of focus. But the connection is, of course Millar. The two novels’ art is similar in the sense of perfectly fitting the writing. The changes in the art correspond directly to the changes in the narrative.

Instead of reveling in super-villains, Kick-Ass looks at super-heroes. Wanted‘s super-villains were created as amalgams of more traditional villains, with references hidden in slogans, details in costume or bearing. The villainy was established by creating a vile protagonist, and making his fellow super-villains even worse. The writing told us what to look for, and the art scattered hints and clues all over the gorgeous pages. Kick-Ass is different. It’s reference to comic antecedents is far more specific and less playful. It doesn’t allow us to distance ourselves from the writing and its implications. A few lines earlier, I called some of Wanted‘s panels “tableaux” – the implied act of leaning back and contemplating a panel or a whole page, this doesn’t quite work for Kick-Ass. The art doesn’t ask you to stop and look, instead its completely immersive, attracts you into its haze of idealism, fear, anxiety and hate. Hate is one of the things that you’ll notice very early on. The narrator doesn’t vocalise his prejudice quite like Wesley, but the art draws your attention to a similar mind-set. In Wanted, the narration needed to be fueled by hate, because the art, due to its detailed realism, suggested impartiality, showing things as they were. Romita Jr.’s art doesn’t even pretend to be impartial. Instead you get sucked into the maelstrom of the protagonist’s teenage mind from the very first panel. Like Wesley, the eponymous Kick-Ass (his mild-mannered name is Dave) moderates the first few panels, telling us what we’re seeing. Unlike Wesley, he abandons narration rather quickly. He doesn’t need to keep it up, however, because the art is clearly doing it for him now. Hate is less expressed and more implied. For instance by the fact that all the villains of the book, and I do mean one hundred percent, are non-white. Latinos, African-Americans, Italian-Americans (for the whiteness of Italian- and Irish-Americans I recommend reading select works of Whiteness Studies (Roediger and others)). The protagonist, on the other hand, is blond. What’s more, he’s ethnically unmarked. As in his best work, Millar uses everything to full effect. We’re never in doubt about the ethnicity of people in the book. Language, color, clothes, all adds to the basic impression: a white blond boy, constantly victimized at school, and, by extension, in his world as well, has enough and fights crime.

Instead of reveling in super-villains, Kick-Ass looks at super-heroes. Wanted‘s super-villains were created as amalgams of more traditional villains, with references hidden in slogans, details in costume or bearing. The villainy was established by creating a vile protagonist, and making his fellow super-villains even worse. The writing told us what to look for, and the art scattered hints and clues all over the gorgeous pages. Kick-Ass is different. It’s reference to comic antecedents is far more specific and less playful. It doesn’t allow us to distance ourselves from the writing and its implications. A few lines earlier, I called some of Wanted‘s panels “tableaux” – the implied act of leaning back and contemplating a panel or a whole page, this doesn’t quite work for Kick-Ass. The art doesn’t ask you to stop and look, instead its completely immersive, attracts you into its haze of idealism, fear, anxiety and hate. Hate is one of the things that you’ll notice very early on. The narrator doesn’t vocalise his prejudice quite like Wesley, but the art draws your attention to a similar mind-set. In Wanted, the narration needed to be fueled by hate, because the art, due to its detailed realism, suggested impartiality, showing things as they were. Romita Jr.’s art doesn’t even pretend to be impartial. Instead you get sucked into the maelstrom of the protagonist’s teenage mind from the very first panel. Like Wesley, the eponymous Kick-Ass (his mild-mannered name is Dave) moderates the first few panels, telling us what we’re seeing. Unlike Wesley, he abandons narration rather quickly. He doesn’t need to keep it up, however, because the art is clearly doing it for him now. Hate is less expressed and more implied. For instance by the fact that all the villains of the book, and I do mean one hundred percent, are non-white. Latinos, African-Americans, Italian-Americans (for the whiteness of Italian- and Irish-Americans I recommend reading select works of Whiteness Studies (Roediger and others)). The protagonist, on the other hand, is blond. What’s more, he’s ethnically unmarked. As in his best work, Millar uses everything to full effect. We’re never in doubt about the ethnicity of people in the book. Language, color, clothes, all adds to the basic impression: a white blond boy, constantly victimized at school, and, by extension, in his world as well, has enough and fights crime.

Fighting crime in Kick-Ass means fighting all the ethnically marked rabble. There is a plethora of critical writing on superhero comics that addresses this question of marked and unmarked actors, and the use and import of wearing a costume, as well as the racial and sexual fault-lines in a tradition that focused on and even expanded notions of masculinity and manliness. Dave is a perfect representation of the fear and anxiety of white males in this new century, afraid to lose privileges and calling frequently for an emancipation for men and accusing people of being racist towards white people. Phenomena like the American Tea Party movement are symptoms of that growing feeling of being threatened by a wave of otherness. And Dave is fighting back. Brilliantly, Millar creates an ambiguous motivation for his protagonist. Dave is beset both by local and global fears, and the local fears are mostly connected to his being a teenager and grappling with the process of growing up. There isn’t enough bile or strength in him to call the adults out, calling them ‘phoneys’. Instead he retreats first into his imagination, and then into violence. In his imagination, as a scrawny comic geek, he learns the symbolic language of comic which works largely through displacement and metaphorical representation. The rhetorical flourishes of right wing attacks, constructing scapegoats, using ideas of purity and evil, Dave has learned all this from comics, in short: he’s perfectly equipped to be a small hateful thug with ideals. There isn’t a patchwork of allusions and references here. There is just one big paradigm in Kick-Ass: it’s Batman. Mostly Frank Miller’s Batman, but Millar uses small details that suggest other Batman-related characters, too. Dave corresponds in many details to the Batman in Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One. The trajectory, from the unsuccessful first bout with criminals which ends with the superheroes-in-waiting bleeding profusely, to the successful second fight and the subsequent establishment, is similar, but what’s more important is that the criminals and the heroes conform to a normal/other dichotomy.

Fighting crime in Kick-Ass means fighting all the ethnically marked rabble. There is a plethora of critical writing on superhero comics that addresses this question of marked and unmarked actors, and the use and import of wearing a costume, as well as the racial and sexual fault-lines in a tradition that focused on and even expanded notions of masculinity and manliness. Dave is a perfect representation of the fear and anxiety of white males in this new century, afraid to lose privileges and calling frequently for an emancipation for men and accusing people of being racist towards white people. Phenomena like the American Tea Party movement are symptoms of that growing feeling of being threatened by a wave of otherness. And Dave is fighting back. Brilliantly, Millar creates an ambiguous motivation for his protagonist. Dave is beset both by local and global fears, and the local fears are mostly connected to his being a teenager and grappling with the process of growing up. There isn’t enough bile or strength in him to call the adults out, calling them ‘phoneys’. Instead he retreats first into his imagination, and then into violence. In his imagination, as a scrawny comic geek, he learns the symbolic language of comic which works largely through displacement and metaphorical representation. The rhetorical flourishes of right wing attacks, constructing scapegoats, using ideas of purity and evil, Dave has learned all this from comics, in short: he’s perfectly equipped to be a small hateful thug with ideals. There isn’t a patchwork of allusions and references here. There is just one big paradigm in Kick-Ass: it’s Batman. Mostly Frank Miller’s Batman, but Millar uses small details that suggest other Batman-related characters, too. Dave corresponds in many details to the Batman in Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One. The trajectory, from the unsuccessful first bout with criminals which ends with the superheroes-in-waiting bleeding profusely, to the successful second fight and the subsequent establishment, is similar, but what’s more important is that the criminals and the heroes conform to a normal/other dichotomy.

The other canonical Miller text on Batman relevant here is his masterful The Dark Knight Returns. In this book, Batman has turned into a hateful muscled old man, disdainful of political correctness and leniency towards criminals, and largely dismissive of democracy. In Kick-Ass, Millar creates the characters of Hit Girl and Big Daddy to reflect that side of being Batman. Like the Cassandra Cain-incarnation of Batgirl, Hit Girl was trained by her father (as Cassandra was trained by hers) to become an excellent killer at a very young age. The rigorous and excessive training has produced a killing machine without many social skills. Without even blinking, Hit Girl slices through hordes of criminals. Neither she nor her father care whether someone is actually guilty of a crime. Being a criminal means being guilty by association. So they kill not just a drug dealer, but also his mistress and all his friends. The utter disdain for human lives and the violent, bracing righteousness connect these two to Miller’s old Batman. Between David, Hit Girl and Big Daddy, Millar has gathered many of the facets of Gotham’s crime-fighter. He has picked up on Miller’s reading of the character as a reactionary, fascist madman, and made a book that reflects that attitude. There is no lee-way in Kick-Ass that would allow for a critical or satiric reading. On the contrary: Mark Millar has, as he does in the best of his books, created an incredibly focused book where every detail is put in the service of one idea. Here it’s right wing hatred. Not criticism of it, but depiction of it, with a clarity and assiduity that makes it almost an anatomy of that attitude. Nothing here is extraneous, everything, the art, dialogue, and the story is extremely focused on one thing and one thing only. In fact, I think that Kick-Ass might well be his best book, because despite the strengths of his other work, this one might just be the most focused and densely told of all his tales.

This is not to deny that his method has its problems. Depicting hate and violence, without even attempting to contain or criticize it, is a risky business and just as The Dark Knight Returns affirms its protagonist’s reactionary values, so does Kick-Ass provide an apology for the dark dreams of Dave. In his review of Haneke’s US remake of Haneke’s own Funny Games, New York Times critic A.O. Scott writes: “voyeuristic masses are implicated in the gruesome spectacle of senseless cruelty. Are we, though? What if the guilt trip never takes off? Or, even worse, what if the American audience, cretins that we are, were to embrace Mr. Haneke’s vision not for its moral stringency but for the thrill of, say, watching Ms. Watts, bound at the ankles and wrists, hop around in her underwear? Who will be implicated then?” This moral ambiguity is characteristic for much of Millar’s work, and while reading him is always an awesome experience, his readers may feel increasingly uneasy. The divide between being a moral writer and an excellent craftsman is not often as wide as it is in Millar’s case. Millar’s work is often problematic and often difficult to stomach, and if we look at the way his oeuvre develops, it seems that there is much more to come. His clean work with the Ultimate X-Men eventually lead to the fascist ambiguities of Civil War, his playful game with hate and villainy in Wanted turned into unfettered racism and violence in Kick-Ass. I am both excited and afraid of what’s to come next from Mark Millar’s busy pen.

This is not to deny that his method has its problems. Depicting hate and violence, without even attempting to contain or criticize it, is a risky business and just as The Dark Knight Returns affirms its protagonist’s reactionary values, so does Kick-Ass provide an apology for the dark dreams of Dave. In his review of Haneke’s US remake of Haneke’s own Funny Games, New York Times critic A.O. Scott writes: “voyeuristic masses are implicated in the gruesome spectacle of senseless cruelty. Are we, though? What if the guilt trip never takes off? Or, even worse, what if the American audience, cretins that we are, were to embrace Mr. Haneke’s vision not for its moral stringency but for the thrill of, say, watching Ms. Watts, bound at the ankles and wrists, hop around in her underwear? Who will be implicated then?” This moral ambiguity is characteristic for much of Millar’s work, and while reading him is always an awesome experience, his readers may feel increasingly uneasy. The divide between being a moral writer and an excellent craftsman is not often as wide as it is in Millar’s case. Millar’s work is often problematic and often difficult to stomach, and if we look at the way his oeuvre develops, it seems that there is much more to come. His clean work with the Ultimate X-Men eventually lead to the fascist ambiguities of Civil War, his playful game with hate and villainy in Wanted turned into unfettered racism and violence in Kick-Ass. I am both excited and afraid of what’s to come next from Mark Millar’s busy pen.

*

As always, if you feel like supporting this blog, there is a “Donate” button on the right. 🙂 If you liked this, tell me. If you hated it, even better. Send me comments, requests or suggestions either below or via email (cf. my About page) or to my twitter.)

Ed Brubaker’s niche, if you will, are comic books nibbling at the borders of masculinity. Some of my favorite works of his involve characters like Daredevil (his run with Michael Lark is probably the best – outside of some of Frank Miller’s work) and Captain America. Coming to terms with violence, balancing responsibility and the inherently transgressive work of superheroes is a constant theme. Outside of his work involving caped crusaders, Brubaker has carved himself a niche writing comic books about crime, usually with his collaborator Sean Phillips doing pencils and ink. I will admit, I am not as interested in these books, particularly those, like Criminal and Incognito, that deal with crime in a doggedly realist way. The first run of Criminal, collected in several trade paperbacks, ended a few years ago – but recently he re-launched the series, collecting the issues by storyline rather than issue by issue. Bad Weekend is, to my mind, the most interesting collection of the bunch. It is not, somehow, about crime at all.

Ed Brubaker’s niche, if you will, are comic books nibbling at the borders of masculinity. Some of my favorite works of his involve characters like Daredevil (his run with Michael Lark is probably the best – outside of some of Frank Miller’s work) and Captain America. Coming to terms with violence, balancing responsibility and the inherently transgressive work of superheroes is a constant theme. Outside of his work involving caped crusaders, Brubaker has carved himself a niche writing comic books about crime, usually with his collaborator Sean Phillips doing pencils and ink. I will admit, I am not as interested in these books, particularly those, like Criminal and Incognito, that deal with crime in a doggedly realist way. The first run of Criminal, collected in several trade paperbacks, ended a few years ago – but recently he re-launched the series, collecting the issues by storyline rather than issue by issue. Bad Weekend is, to my mind, the most interesting collection of the bunch. It is not, somehow, about crime at all.

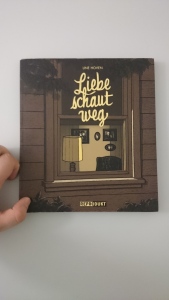

Line Hoven’s art, consisting of stark black-and-white

Line Hoven’s art, consisting of stark black-and-white