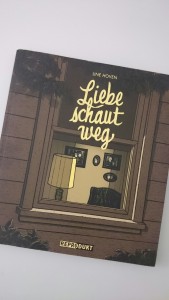

Hoven, Line (2008), Liebe schaut weg, Reprodukt

ISBN 978-3-938511-66-4[Translated into English as Love Looks Away (2014)

Blank Slate Books

ISBN: 978-1-906653-18-7]

The great medievalist Jacques Le Goff, in discussing memory, posits that what we call memory is really an “intersection” of various practices and discourses. Orality, testimony, historiography, and the symbolic structures of what Pierre Nora called “lieux de mémoire” are all part of the process that Le Goff envisioned as being constitutive of ‘memory.’ Photographies have, from the beginning, been part of that process. In a Baudelaire poem, the act of photography is connected to more ancient liminal moments, particularly rites of death, and photos have been part of examinations of witnesses and testimonies throughout the next century, from American agrarian classics of photography to the complex way text and photography interact in WG Sebald’s novels. In the debut graphic novel Love Looks Away by the young artist Line Hoven, there is a complicated representation of truth, personal memory and, to the extent that any public examination of history contributes, of cultural memory, or rather, following Marianne Hirsch, “postmemory”.

The great medievalist Jacques Le Goff, in discussing memory, posits that what we call memory is really an “intersection” of various practices and discourses. Orality, testimony, historiography, and the symbolic structures of what Pierre Nora called “lieux de mémoire” are all part of the process that Le Goff envisioned as being constitutive of ‘memory.’ Photographies have, from the beginning, been part of that process. In a Baudelaire poem, the act of photography is connected to more ancient liminal moments, particularly rites of death, and photos have been part of examinations of witnesses and testimonies throughout the next century, from American agrarian classics of photography to the complex way text and photography interact in WG Sebald’s novels. In the debut graphic novel Love Looks Away by the young artist Line Hoven, there is a complicated representation of truth, personal memory and, to the extent that any public examination of history contributes, of cultural memory, or rather, following Marianne Hirsch, “postmemory”.

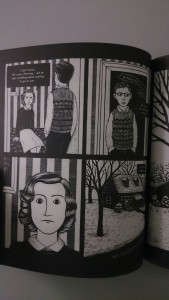

Line Hoven’s art, consisting of stark black-and-white scratchboard or scraperboard art, exquisitely blurs the lines between representations of narrative memory, and between ‘found objects’ like photographs and ticket stubs and other things. The drawing of photographs, thus introducing them into the visual grammar of the artist’s vision, is not part of a Gerhard Richter-like interrogation of representation. On the contrary. I think the book is incredibly disinterested in questions of representation qua representation. Line Hoven’s focus is, almost obsessively, on memory and how getting a family memory ‘right’ can have an impact both on personal as well as collective identities. Hayden White has drawn attention to the way “imagistic” historical representations are “a discourse in its own right” which tells us things “that can only be told by means of visual images.” Love Looks Away is, I think, attempting to do just that, provide a doubly refracted “historiophoty” and the result may be a short book, but reading and rereading it can take a while. It’s been translated into English, but I cannot ascertain the translator’s name. I strongly recommend you acquire and read this book. It is very good. I am personally greatly looking forward to whatever Hoven produces next, given how patient and mature and intelligent -not to mention gorgeous- this first offering is. This artist is going to high places. Get in on the ground floor. Read this book.

Line Hoven’s art, consisting of stark black-and-white scratchboard or scraperboard art, exquisitely blurs the lines between representations of narrative memory, and between ‘found objects’ like photographs and ticket stubs and other things. The drawing of photographs, thus introducing them into the visual grammar of the artist’s vision, is not part of a Gerhard Richter-like interrogation of representation. On the contrary. I think the book is incredibly disinterested in questions of representation qua representation. Line Hoven’s focus is, almost obsessively, on memory and how getting a family memory ‘right’ can have an impact both on personal as well as collective identities. Hayden White has drawn attention to the way “imagistic” historical representations are “a discourse in its own right” which tells us things “that can only be told by means of visual images.” Love Looks Away is, I think, attempting to do just that, provide a doubly refracted “historiophoty” and the result may be a short book, but reading and rereading it can take a while. It’s been translated into English, but I cannot ascertain the translator’s name. I strongly recommend you acquire and read this book. It is very good. I am personally greatly looking forward to whatever Hoven produces next, given how patient and mature and intelligent -not to mention gorgeous- this first offering is. This artist is going to high places. Get in on the ground floor. Read this book.

The English cover features different script from the German one; the result is so much more anodyne. An inexplicable decision. It makes me worry about the way the book’s been translated.

So over the past years I’ve consistently reviewed comic books of all stripes. None of those books, however, were German even though Germany has a fairly vibrant comic scene, plus I’m German, so it would stand to reason they would turn up on my shelves at some point or another. The reason for this absence is that until this year I’ve just never read any. A big loss, as it turns out. Love Looks Away is, as you can probably tell from my very laudatory first paragraph, one of my favorite German comic books, a small, but carefully crafted, powerful graphic memoir. It’s been translated into English in 2014 and published by Blank Slate Books, a publisher who also translated other major German comic book creators like Uli Oesterle or Mawil. Love Looks Away is a book about Line Hoven’s family history, and unfolds, in spare imagery and well spaced episodes, a story that’s more than just one family’s tribulations during and after WWII. It actually ends up providing a convincing picture of a whole generation, despite the unique family circumstances. The story is rooted in Hoven’s grandparents who came of age during the 1940s, and I think this connection allows us to see in the work a kind of exploration of what Marianne Hirsch famously (and importantly) called “postmemory” – a memory of a generation that did not experience historical traumata, but creatively and imaginatively invests in a kind of cultural landscape, a memory created from testimony, but more importantly from objects like photographs, documents and the like. Hirsch’s theory, like many in the area of memory studies, was written to deal with the aftermath of the Shoah specifically, but “postmemory” can really apply to any retroactively created memory of events that are hard to explain or comprehend, usually traumatic. There are things that defy easy channels of recollection, and the process of “postmemory” is one that deals with that, I think, fairly well. I think Derrida referred to the material objects that precede us as the “déja là” – the already here. Hoven’s book starts with what’s already there and her art fills the gaps with a subtle, prodding imagination that stops short of filling in all the psychological questions. This is why I said that her book is primarily about memory: it is not about the “why” of history, personal or political. What it attempts to do is give an artfully heightened account of the things that happened, creating a memory in art.

The gaps are nowhere as obvious as in one of the first sets of family pictures. Throughout the book, the painted copies of photographs are arranged on pages that look like photo albums, with hand written labels, and more. In one of the early “family album” pages, the amorous history of Hoven’s paternal grandparents is represented in four labeled and dated photographs. They met in a Hitler Youth summer camp. That specific photo however is missing, and whether the real photo is genuinely missing, the marked and labeled absence of that photo, shown as a blank space in a photo album, is symbolic of the difficulties of German cultural memory dealing with the more thorny aspects of the nation’s past. Even today, so many year’s later, the events of the time are papered over, guilt is deferred or projected elsewhere. Hoven does not condemn her grandfather, yet neither does she wash him clean of his past. Drawing a blank half page is an indictment of the shame in a suppressed memory. We owe to Martha Langford’s excellentr studies our understanding of how family albums work – as an ersatz oral tradition. Moreover, Hoven’s art in the narrative sections dealing with the past are careful, but sharp. In them, we see a dreaming boy walk proudly and smilingly in his Hitler Youth uniform, and we see a wedding picture where the now young man smiles in a uniform that should not give him reason to be joyful. In a later scene we see that uniformed portrait hanging in a family living room. Hoven’s work consists of scenes with little connecting tissue except for the drawn pages from a family album. It depends on her reader’s sense of history, on our sense of contexts and motivations. According to Martha Langford, reading family albums is an interpretative performance. We all, strangers or actual family, create narratives around the arranged photographs, as Langford found. If we understand this to be part of the underlying oral structure of photographs, then Hoven’s sparse illustrations, low as they are on explanation, have a very similar effect. We get more story than we would from photos, but the isolated effect is very similar.

The gaps are nowhere as obvious as in one of the first sets of family pictures. Throughout the book, the painted copies of photographs are arranged on pages that look like photo albums, with hand written labels, and more. In one of the early “family album” pages, the amorous history of Hoven’s paternal grandparents is represented in four labeled and dated photographs. They met in a Hitler Youth summer camp. That specific photo however is missing, and whether the real photo is genuinely missing, the marked and labeled absence of that photo, shown as a blank space in a photo album, is symbolic of the difficulties of German cultural memory dealing with the more thorny aspects of the nation’s past. Even today, so many year’s later, the events of the time are papered over, guilt is deferred or projected elsewhere. Hoven does not condemn her grandfather, yet neither does she wash him clean of his past. Drawing a blank half page is an indictment of the shame in a suppressed memory. We owe to Martha Langford’s excellentr studies our understanding of how family albums work – as an ersatz oral tradition. Moreover, Hoven’s art in the narrative sections dealing with the past are careful, but sharp. In them, we see a dreaming boy walk proudly and smilingly in his Hitler Youth uniform, and we see a wedding picture where the now young man smiles in a uniform that should not give him reason to be joyful. In a later scene we see that uniformed portrait hanging in a family living room. Hoven’s work consists of scenes with little connecting tissue except for the drawn pages from a family album. It depends on her reader’s sense of history, on our sense of contexts and motivations. According to Martha Langford, reading family albums is an interpretative performance. We all, strangers or actual family, create narratives around the arranged photographs, as Langford found. If we understand this to be part of the underlying oral structure of photographs, then Hoven’s sparse illustrations, low as they are on explanation, have a very similar effect. We get more story than we would from photos, but the isolated effect is very similar.

This style of memory and writing is further emphasized by the book’s use of language. Hoven’s father, Reinhard is German, but her mother Charlotte is American, and the family history offers us both sets of grandparents – who do not, obviously speak German (in fact, Charlotte’s father has an almost pathological hatred of Germans, which is partly rooted in his inability to enlist in WWII due to health issues). Charlotte herself frequently speaks English in the book. Hoven does not translate or annotate any of the English dialog. The book is, in this sense, completely bilingual. Anything that was German when it happened, is rendered in German by Hoven, and everything that was English is rendered as English. This only further emphasizes the near-documentary narrative ethos of Hoven’s work of “postmemory.” The documentary effect does not, however, really extend to backgrounds. I mentioned Nora at the outset, but the book isn’t incredibly concerned with places of memory. I am not entirely sure how strong even the sense of place is? Much of the book is set in Bonn, the former capital of (West) Germany, and since I also live in Bonn, I recognize the vast majority of facades and buildings we see, but I am not sure that for someone who does not intimately know this cooky little West German city, the sense of place is particularly strong here. Hoven does not connect her visualization of memory, or postmemory, to commonly shared buildings. Evading obvious landmarks that are understood across a shared culture is done so thoroughly that it seems almost intentional. One of the “family album” pages shows a foto of family members standing in front of the Cologne Cathedral, which is one of Germany’s most famous buildings, yet the angle only includes part of the front door, as you would in a family picture. There is no wide pan to include the whole building and unless you have been there a few times and will recognize it even from this small snippet, the building will, at best, say “some big cathedral.” The exteriors of Bonn, similarly, are obvious to me (and extremely carefully and precisely rendered), but evade some of the most obvious landmarks.

This style of memory and writing is further emphasized by the book’s use of language. Hoven’s father, Reinhard is German, but her mother Charlotte is American, and the family history offers us both sets of grandparents – who do not, obviously speak German (in fact, Charlotte’s father has an almost pathological hatred of Germans, which is partly rooted in his inability to enlist in WWII due to health issues). Charlotte herself frequently speaks English in the book. Hoven does not translate or annotate any of the English dialog. The book is, in this sense, completely bilingual. Anything that was German when it happened, is rendered in German by Hoven, and everything that was English is rendered as English. This only further emphasizes the near-documentary narrative ethos of Hoven’s work of “postmemory.” The documentary effect does not, however, really extend to backgrounds. I mentioned Nora at the outset, but the book isn’t incredibly concerned with places of memory. I am not entirely sure how strong even the sense of place is? Much of the book is set in Bonn, the former capital of (West) Germany, and since I also live in Bonn, I recognize the vast majority of facades and buildings we see, but I am not sure that for someone who does not intimately know this cooky little West German city, the sense of place is particularly strong here. Hoven does not connect her visualization of memory, or postmemory, to commonly shared buildings. Evading obvious landmarks that are understood across a shared culture is done so thoroughly that it seems almost intentional. One of the “family album” pages shows a foto of family members standing in front of the Cologne Cathedral, which is one of Germany’s most famous buildings, yet the angle only includes part of the front door, as you would in a family picture. There is no wide pan to include the whole building and unless you have been there a few times and will recognize it even from this small snippet, the building will, at best, say “some big cathedral.” The exteriors of Bonn, similarly, are obvious to me (and extremely carefully and precisely rendered), but evade some of the most obvious landmarks.

I mean, all of this seems hyperfocused. I have not really discussed the smaller stories here because there is so little narrative that I think you should let yourself be surprised by it. I assure you, you’ll like this book, if you like this kind of stuff at all. And I haven’t even mentioned the art at all. Like all the content aspects, the art also contributes to the book’s theme. The art consists of black and white scraperboard etchings (see wiki for details). The effect is really interesting. It creates an interesting dynamic that strongly interacts with the static structure of the book, the photographs and all that, and it also allows us to read the book in a certain German artistic continuum. There is a lot of historically and politically heightened art with similar effects – I mean, it strongly echoes some stark 20th century woodcuts, and in many pictures here I think has a conversation with German expressionist woodcuts (think Ernst Barlach). Another well known/excellent contemporary German cartoonist who employs this scratchboard technique (and hews closer to the German expressionist tradition) is Thomas Ott. Look, I know this review discusses memory studies a lot, and it seems as if I am less interested in the art, but everything I described hinges on Hoven’s art. Fundamentally, the biggest and most entrancing aspect of the book IS the art. Hoven has been working on that art in the years since the publication too, picking up awards, exhibitions and I will read whatever book comes next. It is also the art that sets her apart from many of her German peers. Much of German art is influenced by American underground comix, with some extremely notable and excellent exceptions (the unbelievable Peer Meter comes to mind, who also, incidentally, works on memory and history). Line Hoven is in the process of carving out a space of her own.

I mean, all of this seems hyperfocused. I have not really discussed the smaller stories here because there is so little narrative that I think you should let yourself be surprised by it. I assure you, you’ll like this book, if you like this kind of stuff at all. And I haven’t even mentioned the art at all. Like all the content aspects, the art also contributes to the book’s theme. The art consists of black and white scraperboard etchings (see wiki for details). The effect is really interesting. It creates an interesting dynamic that strongly interacts with the static structure of the book, the photographs and all that, and it also allows us to read the book in a certain German artistic continuum. There is a lot of historically and politically heightened art with similar effects – I mean, it strongly echoes some stark 20th century woodcuts, and in many pictures here I think has a conversation with German expressionist woodcuts (think Ernst Barlach). Another well known/excellent contemporary German cartoonist who employs this scratchboard technique (and hews closer to the German expressionist tradition) is Thomas Ott. Look, I know this review discusses memory studies a lot, and it seems as if I am less interested in the art, but everything I described hinges on Hoven’s art. Fundamentally, the biggest and most entrancing aspect of the book IS the art. Hoven has been working on that art in the years since the publication too, picking up awards, exhibitions and I will read whatever book comes next. It is also the art that sets her apart from many of her German peers. Much of German art is influenced by American underground comix, with some extremely notable and excellent exceptions (the unbelievable Peer Meter comes to mind, who also, incidentally, works on memory and history). Line Hoven is in the process of carving out a space of her own.

*

As always, if you feel like supporting this blog, there is a “Donate” button on the left and this link RIGHT HERE. If you liked this, tell me. If you hated it, even better. Send me comments, requests or suggestions either below or via email (cf. my About page) or to my twitter.)