Miéville, China; Mateus Santolouco, Riccardo Burchielli et al. (2013), Dial H: Into You, DC Comics

ISBN 9-781401-237752

Wood, Dave; Jim Mooney et al. (2010), Showcase Presents: Dial H for Hero, DC Comics

ISBN 978-1-4012-2648-0

Pfeifer, Will; Kano et al. (2003), H-E-R-O: Powers and Abilities, DC Comics

ISBN 1-4012-0168-7

So, while I am a fan of comic books and do read quite a few of them, I am still frequently overwhelmed by the incredible amount of characters and complicated back stories. DC Comics is especially infamous for not just having complicated stories, but even multiple realities and universes, which they then attempted to collapse in amazingly readable and fun but convoluted “events”. Then, suddenly, DC decided to do away with all the accrued history and complications by relaunching all of its titles in 2011, calling the new set of books “the new 52”. This reset the stories on all their major titles, giving them new origin stories, and new slants. It also turned the DC universe somewhat more male, due to the fact that female creators were vastly underrepresented among the slate of amazing writers and artists, and also due to the fact that a lot of female characters either completely vanished, like fan favorite Stephanie Brown, or were declared dead, like Renée Montoya. Other female characters were revived as weaker or “sexier” versions of their old selves. And it’s not just female characters. The first waves of comics to come out seemed to have a decidedly conservative slant in how they were positioned vis-a-vis recent character history. One example is Judd Winnick’s Catwoman run, as compared to the more recent history of the character in the hands of Ed Brubaker, Darwyn Cooke and others. However, DC also did something very interesting: they decided to use the bright lights of public attention in the wake of the relaunch in order to relaunch a bunch of much less well known characters, some of whom were pulled from DC’s more alternative imprints Vertigo and Wildstorm.

So, while I am a fan of comic books and do read quite a few of them, I am still frequently overwhelmed by the incredible amount of characters and complicated back stories. DC Comics is especially infamous for not just having complicated stories, but even multiple realities and universes, which they then attempted to collapse in amazingly readable and fun but convoluted “events”. Then, suddenly, DC decided to do away with all the accrued history and complications by relaunching all of its titles in 2011, calling the new set of books “the new 52”. This reset the stories on all their major titles, giving them new origin stories, and new slants. It also turned the DC universe somewhat more male, due to the fact that female creators were vastly underrepresented among the slate of amazing writers and artists, and also due to the fact that a lot of female characters either completely vanished, like fan favorite Stephanie Brown, or were declared dead, like Renée Montoya. Other female characters were revived as weaker or “sexier” versions of their old selves. And it’s not just female characters. The first waves of comics to come out seemed to have a decidedly conservative slant in how they were positioned vis-a-vis recent character history. One example is Judd Winnick’s Catwoman run, as compared to the more recent history of the character in the hands of Ed Brubaker, Darwyn Cooke and others. However, DC also did something very interesting: they decided to use the bright lights of public attention in the wake of the relaunch in order to relaunch a bunch of much less well known characters, some of whom were pulled from DC’s more alternative imprints Vertigo and Wildstorm.

Frankenstein, for example, last seen in Grant Morrison’s book Seven Soldiers of Victory, was given his own title (written by the great, great Jeff Lemire), as were Animal Man and Swamp Thing, both of whom had iconic runs with Vertigo. The characters thus revived are not all equally well known. While Swamp Thing is probably one of the best known ‘alternative’ properties of DC, they also offered much less well known characters and titles a spot in the limelight. One of these characters/properties is Dial H for Hero, a decidedly odd kind of title, with a very inconsistent publishing history. His revival could have gone either way. DC, however, asked China Miéville to write this title, and the result is incredibly good. I have been reading quite a few comic books during the past year, and some extremely good ones among them (I’ll probably review some of them in the near future), but Miéville’s Dial H is easily one of the best, if not the best among this crop of really excellent comics that have been coming out. If you have been following Miéville’s career (as I have), this will likely not have come as a surprise to you. Miéville has established himself as one of the leading contemporary writers of science fiction, and probably one of the better novelists in the UK regardless of genre. Even considering the regrettable duds like Kraken, his bibliography is full of inventive, smart, extraordinarily well written novels. The news that he would be turning his attention to comic books in order to write a title of his own had me giddy and excited for a year. I spent part of that year reading up on the history of the character or characters that would be featured in Miéville’s book. And as I found out, that is a peculiar history.

Frankenstein, for example, last seen in Grant Morrison’s book Seven Soldiers of Victory, was given his own title (written by the great, great Jeff Lemire), as were Animal Man and Swamp Thing, both of whom had iconic runs with Vertigo. The characters thus revived are not all equally well known. While Swamp Thing is probably one of the best known ‘alternative’ properties of DC, they also offered much less well known characters and titles a spot in the limelight. One of these characters/properties is Dial H for Hero, a decidedly odd kind of title, with a very inconsistent publishing history. His revival could have gone either way. DC, however, asked China Miéville to write this title, and the result is incredibly good. I have been reading quite a few comic books during the past year, and some extremely good ones among them (I’ll probably review some of them in the near future), but Miéville’s Dial H is easily one of the best, if not the best among this crop of really excellent comics that have been coming out. If you have been following Miéville’s career (as I have), this will likely not have come as a surprise to you. Miéville has established himself as one of the leading contemporary writers of science fiction, and probably one of the better novelists in the UK regardless of genre. Even considering the regrettable duds like Kraken, his bibliography is full of inventive, smart, extraordinarily well written novels. The news that he would be turning his attention to comic books in order to write a title of his own had me giddy and excited for a year. I spent part of that year reading up on the history of the character or characters that would be featured in Miéville’s book. And as I found out, that is a peculiar history.

Limited as I am to trade publications, I will focus on only two books centered on the “Dial H”-property. There were small instances of the title resurfacing in between, they were not, however, collected as trades. The first time comic book readers came upon the Dial H for Hero stories was in 1965, in the pages of “House of Mystery #165”. The stories featured a boy called Robby Reed who finds a strange apparatus that “looks like a dial…made of a peculiar alloy….with a strange inscription on it”. The “young genius” decipers the inscription running along the side of the apparatus and finds that it asks its user to “dial the letters h-e-r-o”. Intrepid young Robby Reed does just that and, lo and behold, he turns into a superhero. His whole physical appearance is transformed: he has become a giant, complete with a superhero uniform (that even has letters on the front) and somehow he knows that the hero he transformed into is called “Giantboy”. Using the powers of the character, he thwarts some evil villains, and returning home, dials o-r-e-h in order to transform back into his bespectacled mild mannered self. The boy turning into an adult superhero is highly reminiscent of DC’s Captain Marvel, which is a boy called Billy Bateson who turns into the superhero Captain Marvel by saying “Shazam!”. However, as far as I know, Captain Marvel (sometimes also just named “Shazam”) is always more or less the same guy. Robby Reed’s dial, however, turns him into a different superhero every time he gives his dial a spin. There is so much that is bad about this title, from the casual racism (at one point he turns into “an Indian super-hero – Chief Mighty Arrow” and is even issued a companion, “a winged injun pony”. When he is upset, he shouts “Holy Massacre” and wishes he could “scalp” a monster) to sexism (Robby’s love interest find the dial, dials “h-e-r-o-i-n-e” and turns into “Gem Girl” despite Robby’s warnings that the dial is not a toy, and he ends up forcing her to dial herself back into a girl “before she gets any more ideas”), and overall ridiculous writing. However, it’s some of the most incredibly inventive work I have ever seen.

Limited as I am to trade publications, I will focus on only two books centered on the “Dial H”-property. There were small instances of the title resurfacing in between, they were not, however, collected as trades. The first time comic book readers came upon the Dial H for Hero stories was in 1965, in the pages of “House of Mystery #165”. The stories featured a boy called Robby Reed who finds a strange apparatus that “looks like a dial…made of a peculiar alloy….with a strange inscription on it”. The “young genius” decipers the inscription running along the side of the apparatus and finds that it asks its user to “dial the letters h-e-r-o”. Intrepid young Robby Reed does just that and, lo and behold, he turns into a superhero. His whole physical appearance is transformed: he has become a giant, complete with a superhero uniform (that even has letters on the front) and somehow he knows that the hero he transformed into is called “Giantboy”. Using the powers of the character, he thwarts some evil villains, and returning home, dials o-r-e-h in order to transform back into his bespectacled mild mannered self. The boy turning into an adult superhero is highly reminiscent of DC’s Captain Marvel, which is a boy called Billy Bateson who turns into the superhero Captain Marvel by saying “Shazam!”. However, as far as I know, Captain Marvel (sometimes also just named “Shazam”) is always more or less the same guy. Robby Reed’s dial, however, turns him into a different superhero every time he gives his dial a spin. There is so much that is bad about this title, from the casual racism (at one point he turns into “an Indian super-hero – Chief Mighty Arrow” and is even issued a companion, “a winged injun pony”. When he is upset, he shouts “Holy Massacre” and wishes he could “scalp” a monster) to sexism (Robby’s love interest find the dial, dials “h-e-r-o-i-n-e” and turns into “Gem Girl” despite Robby’s warnings that the dial is not a toy, and he ends up forcing her to dial herself back into a girl “before she gets any more ideas”), and overall ridiculous writing. However, it’s some of the most incredibly inventive work I have ever seen.

Robby transforms into heroes that make sense, like Giantboy or The Human Bullet etc., but in one issue he transforms into geometric shapes with arms and legs, for example. Coming up with new heroes (although you can dial up old ones too, it’s basically a randomized selection out of a finite, but large pool) forced the writer of the books, Dave Wood, to dig deep. And Jim Mooney’s art perfectly realizes Wood’s wacky vision. It’s just so much ridiculous fun, and the Showcase volume is well worth your while. If you want an idea of the silly fun on offer, click here to see a selection of covers. After a while the Dial H for Hero stories petered out. There were various small scale revivals, including one in the 1980s by the great Marv Wolfman, also called Dial H for Hero, but since none of them have been published as trades, I can’t really comment on them. They introduced more characters spinning the dial and further enlarged the pool of super-heroes. I’ve had a look at the Wiki summary of Wolfman’s run and it seems delightfully insane, and it seems to have more of a coherent plot than the Wood/Mooney version, which is basically a gonzo one-off kind of thing in each issue.

Robby transforms into heroes that make sense, like Giantboy or The Human Bullet etc., but in one issue he transforms into geometric shapes with arms and legs, for example. Coming up with new heroes (although you can dial up old ones too, it’s basically a randomized selection out of a finite, but large pool) forced the writer of the books, Dave Wood, to dig deep. And Jim Mooney’s art perfectly realizes Wood’s wacky vision. It’s just so much ridiculous fun, and the Showcase volume is well worth your while. If you want an idea of the silly fun on offer, click here to see a selection of covers. After a while the Dial H for Hero stories petered out. There were various small scale revivals, including one in the 1980s by the great Marv Wolfman, also called Dial H for Hero, but since none of them have been published as trades, I can’t really comment on them. They introduced more characters spinning the dial and further enlarged the pool of super-heroes. I’ve had a look at the Wiki summary of Wolfman’s run and it seems delightfully insane, and it seems to have more of a coherent plot than the Wood/Mooney version, which is basically a gonzo one-off kind of thing in each issue.

Even more coherent (and initially at least considerably more down to earth) is the 2003 incarnation called H-E-R-O, written by Will Pfeifer and beautifully illustrated by Kano. That run went on for 22 issues, but for some reason, only issues 1-6 have been collected as a trade (called H-E-R-O: Powers and Abilities). Pfeifer’s run features different people finding the dial and examines what happens to their lives when you add the opportunity to transform into a superhero. There is a young adult mired in a mediocre life, “making sundaes at minimum wage”. In order to impress a girl, and more generally as an attempt to “be someone”, he uses the Dial to unimpressive and even disastrous effect. A business man finding the dial becomes obsessed with it. A girl uses it to become popular at her new school, etc. The book was a bit of a letdown, even though the writing and art was just so much better than the Wood/Mooney version. But Pfeifer got rid of the ridiculous fun and inventiveness and infused the whole book with a dour morality, mostly lectures about being content with who you are and knowing your limits and being nice and industrious within those limits. Much more than the original book, the dialing device becomes a metaphor for situations that we all face in our lives etc. etc. I’m boring myself just describing it. For all the good writing and wonderful art that went into this book, it’s hard to recommend, because Pfeifer so consistently underwhelms. The idea of the dial is one of the most liberating literary devices I have ever seen, and to see it used in this pedestrian, moral, middle-class way was disheartening. If that was the direction that the Dial H for Hero story was going, I was worried about Miéville’s run presenting more of the same. Silly me. China Miéville blows Pfeifer’s run clean out of the water.

Even more coherent (and initially at least considerably more down to earth) is the 2003 incarnation called H-E-R-O, written by Will Pfeifer and beautifully illustrated by Kano. That run went on for 22 issues, but for some reason, only issues 1-6 have been collected as a trade (called H-E-R-O: Powers and Abilities). Pfeifer’s run features different people finding the dial and examines what happens to their lives when you add the opportunity to transform into a superhero. There is a young adult mired in a mediocre life, “making sundaes at minimum wage”. In order to impress a girl, and more generally as an attempt to “be someone”, he uses the Dial to unimpressive and even disastrous effect. A business man finding the dial becomes obsessed with it. A girl uses it to become popular at her new school, etc. The book was a bit of a letdown, even though the writing and art was just so much better than the Wood/Mooney version. But Pfeifer got rid of the ridiculous fun and inventiveness and infused the whole book with a dour morality, mostly lectures about being content with who you are and knowing your limits and being nice and industrious within those limits. Much more than the original book, the dialing device becomes a metaphor for situations that we all face in our lives etc. etc. I’m boring myself just describing it. For all the good writing and wonderful art that went into this book, it’s hard to recommend, because Pfeifer so consistently underwhelms. The idea of the dial is one of the most liberating literary devices I have ever seen, and to see it used in this pedestrian, moral, middle-class way was disheartening. If that was the direction that the Dial H for Hero story was going, I was worried about Miéville’s run presenting more of the same. Silly me. China Miéville blows Pfeifer’s run clean out of the water.

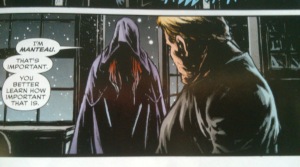

Miéville renames the series Dial H, and provides a spin on it that is equal parts original and respectful to the Silver Age original. The protagonist of the first trade is called Nelson Jent, and he’s an obese unemployed middle aged man, who, one night, is almost beat up by a group of lowlifes and, attempting to call the police from a phone booth, transforms into Boy Chimney. From that moment the reader knows that this is something else than the other titles in the Dial H for Hero series. And it starts with small details: Mieville, like many writers, offers us the thoughts of the characters that he focuses on. And as Jent transforms into Boy Chimney, his thoughts seem to transform, as well. Strange fragments enter them, and as Boy Chimney proceeds to beat up that gang, he appears to have a dialog with the consciousness of Nelson Jent. Additionally, Boy Chimney is very clearly not a super hero, as all the previous titles imagined them. He is a strange creature that has uncommon strength and unusual powers and abilities, among them the ability to use and command smoke. But it’s only Jent’s consciousness that keeps Boy Chimney from outright killing the brutal assailants in the alley. It feels less like Jent is genuinely transforming into a super hero, and more like a kind of symbiosis. And there is another basic difference: Jent doesn’t have to transform back by dialing the letters in reverse. He automatically returns to his normal self, “into the worst identity of all”, after a certain, variable amount of time has passed. Apart from this, the book’s early parts seem to be fairly straightforward. There’s a villain with a secret plan and he and Jent’s super heroes keep meeting and fighting. And then, the book quickly goes off the rails into the most incredible insanity. The villain, it turns out, is a “nullomancer”, a kind of wizard of nothingness, able to conjure and control nothingness, and her plan involves channeling an ancient beast called the Abyss, a strange thing composed of nothingness, but at the same time, containing universes.

Miéville renames the series Dial H, and provides a spin on it that is equal parts original and respectful to the Silver Age original. The protagonist of the first trade is called Nelson Jent, and he’s an obese unemployed middle aged man, who, one night, is almost beat up by a group of lowlifes and, attempting to call the police from a phone booth, transforms into Boy Chimney. From that moment the reader knows that this is something else than the other titles in the Dial H for Hero series. And it starts with small details: Mieville, like many writers, offers us the thoughts of the characters that he focuses on. And as Jent transforms into Boy Chimney, his thoughts seem to transform, as well. Strange fragments enter them, and as Boy Chimney proceeds to beat up that gang, he appears to have a dialog with the consciousness of Nelson Jent. Additionally, Boy Chimney is very clearly not a super hero, as all the previous titles imagined them. He is a strange creature that has uncommon strength and unusual powers and abilities, among them the ability to use and command smoke. But it’s only Jent’s consciousness that keeps Boy Chimney from outright killing the brutal assailants in the alley. It feels less like Jent is genuinely transforming into a super hero, and more like a kind of symbiosis. And there is another basic difference: Jent doesn’t have to transform back by dialing the letters in reverse. He automatically returns to his normal self, “into the worst identity of all”, after a certain, variable amount of time has passed. Apart from this, the book’s early parts seem to be fairly straightforward. There’s a villain with a secret plan and he and Jent’s super heroes keep meeting and fighting. And then, the book quickly goes off the rails into the most incredible insanity. The villain, it turns out, is a “nullomancer”, a kind of wizard of nothingness, able to conjure and control nothingness, and her plan involves channeling an ancient beast called the Abyss, a strange thing composed of nothingness, but at the same time, containing universes.

If this sounds absurd, I can assure you that Miéville makes it work on the page, and in his origin story, which closes out the trade, he offers a brilliant explanation for what the dial basically does. It’s hard to give you more details without spoiling the book, so I won’t, but the upshot of it all is that Miéville managed to tell a story that makes use of the incredible artistic liberties that the material has to offer, and yet it’s a book very determined to make sense, in multiple ways. What’s more, the art is not a let down. Would it have been a better book with JH Williams III at the helm? Possibly. But Mateus Santolouco, of whom I have never heard, does an excellent job. I was especially impressed by his work on the super-hero identities invoked by the dial. They are the most crucial visual element of the book, as they have to appear both plausible and iconical – and absurdly odd at the same time. As Boy Chimney leaps from the phone booth he is instantly alive on the page, as a scary, off the wall character. Almost as important are the colors, and Tanya and Richard Horie have done a simply magnificent job throughout the book. In my review of Brian Wood’s DMZ I have lamented the fact that the art seemed but a servant to Wood’s writing in the book, making for a less than great reading experience. That is not the case with Dial H. Even though Miéville is a famous award winning novelist, Santolouco brings a very distinct artistic vision to bear. The sketches in the back show how he worked on and tweaked the look of various superhero identities. Santolouco’s achievement is thrown into even starker relief by issue #0, which presents a kind of origin story, and is included at the back of the trade. Riccardo Burchielli valiantly tries to do justice to Miéville’s amazing script, but it’s an overall disappointing effort, compared to Santolouco’s work that came before.

If this sounds absurd, I can assure you that Miéville makes it work on the page, and in his origin story, which closes out the trade, he offers a brilliant explanation for what the dial basically does. It’s hard to give you more details without spoiling the book, so I won’t, but the upshot of it all is that Miéville managed to tell a story that makes use of the incredible artistic liberties that the material has to offer, and yet it’s a book very determined to make sense, in multiple ways. What’s more, the art is not a let down. Would it have been a better book with JH Williams III at the helm? Possibly. But Mateus Santolouco, of whom I have never heard, does an excellent job. I was especially impressed by his work on the super-hero identities invoked by the dial. They are the most crucial visual element of the book, as they have to appear both plausible and iconical – and absurdly odd at the same time. As Boy Chimney leaps from the phone booth he is instantly alive on the page, as a scary, off the wall character. Almost as important are the colors, and Tanya and Richard Horie have done a simply magnificent job throughout the book. In my review of Brian Wood’s DMZ I have lamented the fact that the art seemed but a servant to Wood’s writing in the book, making for a less than great reading experience. That is not the case with Dial H. Even though Miéville is a famous award winning novelist, Santolouco brings a very distinct artistic vision to bear. The sketches in the back show how he worked on and tweaked the look of various superhero identities. Santolouco’s achievement is thrown into even starker relief by issue #0, which presents a kind of origin story, and is included at the back of the trade. Riccardo Burchielli valiantly tries to do justice to Miéville’s amazing script, but it’s an overall disappointing effort, compared to Santolouco’s work that came before.

The book has so many ideas, and one of them is an obsession with identity. With superheroes, we talk a lot about identities, secret and public ones, but that is usually a naming issue: what name do I use? What mask do I wear. Alternative takes on superhero narratives (cf. Millar’s Kick-Ass) suggest that wearing masks is liberating, but they don’t really discuss or problematize the core issue of identity. Miéville, as all his work so far has also shown, is very aware of how identity is tied up in physical forms and in cultural and social ties. The characters that Jent turns into appear to have their own memories, and while it turns out to be an issue more of colonialism and appropriation than of sociology and psychology, Miéville opens wide the doors for these discussions. In doing so, I think, he goes beyond even writers like Morrison, as he uses the iconicity and language of big publisher super-hero comics and examines it carefully. This is not another one of those books critical of ‘superhero myths’, and it doesn’t offer a grimy reality based taken on super heroes. There are enough of those around. No, Miéville embraces a lot of the central qualities of the genre and uses its language in order to interrogate it and tell an absorbing story at the same time. The best news? There is much more to come. For all the density of this book, it merely collects the first issues in an ongoing run. The next trade is due in January 2014. You should be reading this book.

The book has so many ideas, and one of them is an obsession with identity. With superheroes, we talk a lot about identities, secret and public ones, but that is usually a naming issue: what name do I use? What mask do I wear. Alternative takes on superhero narratives (cf. Millar’s Kick-Ass) suggest that wearing masks is liberating, but they don’t really discuss or problematize the core issue of identity. Miéville, as all his work so far has also shown, is very aware of how identity is tied up in physical forms and in cultural and social ties. The characters that Jent turns into appear to have their own memories, and while it turns out to be an issue more of colonialism and appropriation than of sociology and psychology, Miéville opens wide the doors for these discussions. In doing so, I think, he goes beyond even writers like Morrison, as he uses the iconicity and language of big publisher super-hero comics and examines it carefully. This is not another one of those books critical of ‘superhero myths’, and it doesn’t offer a grimy reality based taken on super heroes. There are enough of those around. No, Miéville embraces a lot of the central qualities of the genre and uses its language in order to interrogate it and tell an absorbing story at the same time. The best news? There is much more to come. For all the density of this book, it merely collects the first issues in an ongoing run. The next trade is due in January 2014. You should be reading this book.

*

As always, if you feel like supporting this blog, there is a “Donate” button on the right. I really need it 🙂 If you liked this, tell me. If you hated it, even better. Send me comments, requests or suggestions either below or via email (cf. my About page) or to my twitter.)