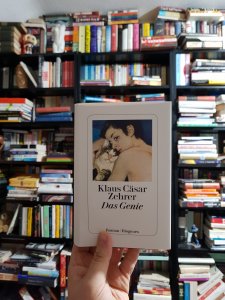

Gomringer, Nora (2017), Moden, Voland & Quist

ISBN 978-3-86391-169-0

The most prestigious German-language literary award is the Büchner Preis. It is not given for a single work, it’s given for a whole oeuvre. Sometimes it’s given to younger writers, sometimes older writers, very often it’s well judged. I don’t get miffed about its choices often. Sometimes it even surprises me, as when the award was given to Felicitas Hoppe, a fiendishly clever novelist with a small but excellent body of work. Sometimes it goes to writers who should have won it a decade ago. Jürgen Becker and Marcel Beyer are examples of overdue writers finally getting their due in these past years. The award, unlike the Nobel Prize in Literature, actually awards poets quite often. Becker is an example of an important poet winning the award. If you want to read his work, you’re fortunate that the late Okla Elliott has translated a selection of his shorter poems, published by Black Lawrence Press. But, and obviously, that’s just me, it’s the awards for small forms, poets, writers of novellas that sometimes misfire. Wolfdietrich Schnurre, Büchner laureate in the 80s, was an important writer of postwar literature, particularly well known for his short stories, but exceedingly minor today. I am also not convinced of the plaudits frequently awarded to Durs Grünberg, whose debut collection of poetry I adore, but that’s about the only collection of his that is genuinely great.

The most prestigious German-language literary award is the Büchner Preis. It is not given for a single work, it’s given for a whole oeuvre. Sometimes it’s given to younger writers, sometimes older writers, very often it’s well judged. I don’t get miffed about its choices often. Sometimes it even surprises me, as when the award was given to Felicitas Hoppe, a fiendishly clever novelist with a small but excellent body of work. Sometimes it goes to writers who should have won it a decade ago. Jürgen Becker and Marcel Beyer are examples of overdue writers finally getting their due in these past years. The award, unlike the Nobel Prize in Literature, actually awards poets quite often. Becker is an example of an important poet winning the award. If you want to read his work, you’re fortunate that the late Okla Elliott has translated a selection of his shorter poems, published by Black Lawrence Press. But, and obviously, that’s just me, it’s the awards for small forms, poets, writers of novellas that sometimes misfire. Wolfdietrich Schnurre, Büchner laureate in the 80s, was an important writer of postwar literature, particularly well known for his short stories, but exceedingly minor today. I am also not convinced of the plaudits frequently awarded to Durs Grünberg, whose debut collection of poetry I adore, but that’s about the only collection of his that is genuinely great.

And last year, the award was given, I don’t know why, to Jan Wagner. Jan Wagner is commonly credited with resurrecting popular poetry in Germany. His 2014 collection Regentonnenvariationen (~Rain Barrel Variations) rose to the top of the bestseller list, he won all kinds of awards, it was quite intense for a while. But his work is exceedingly banal. It’s what you’d expect from a well educated, smooth young man. The poetry is well crafted, tonally frequently epigonal, to the point where individual lines shift in debt from Grass, to Eich, to Fried. More than once I thought I recognized the actual wording and pulled Grass, Eich or Fried from my shelves, but of course that was never it. It’s just the echoes you can expect in the work of a gifted reader and craftsman. I don’t know who to compare it to. Maybe: what if Mary Oliver was less interesting.

Ok, ok. This is not about Wagner. But if you wanted to give a brilliant younger poet an award last year (to be quite honest, I don’t see how a writer like, say, Robert Schindel or Natascha Wodin wouldn’t be at the top of any Büchnerpreislist, but that’s not the point), I wouldn’t have picked Wagner. I would have picked Nora Gomringer. Nora Gomringer is a poet with a big name, as her father Eugen Gomringer is one of the most important German poets of the 20th century. That’s a heavy cross to bear, but Nora Gomringer wears that burden well. She has produced consistently good work, on stage, on the page, and she has supported and pushed other artists. She’s won a ton of awards, among which most recently, in 2015, the Bachmannpreis. For prose, of course, because why the fuck not. Nora Gomringer can do a lot of things, but what’s most remarkable is her gift for poetry.

I don’t do poetry reviews on this blog a lot. In fact, I think this review of Ben Mazer’s book is the only one I did. But on this, the final day of #GermanLitMonth I was re-reading her most recent book, the most excellent Moden, and thought, why not. I will say this: poetry reviews are difficult for me because I always put them in relation to my own writing; not a comparison, but I have a fairly good sense right now of what kind of idiom comes easy to me and what doesn’t, etc. So when I read Nora Gomringer’s recent books, one thing that stuns me in particular is the way she is able to control colloquialism and sharp, arch tone and turns of phrases. In German poetry, when you try to combine these two elements, what you usually do, see Wagner, is sound a lot like Grass. Because Grass (read my brief post about him here) perfected a specific way to turn words around, estrange them from common usage, spin, color them, in particular verbs. Moving them through sentences, conjugating them against the grain – when Grass was good, he was brilliant. But ever since, writers who tried to lift words into art have often reached for Grass’s register. It’s incredibly seductive. It works fantastically well.

Nora Gomringer doesn’t do that. And even after reading her book multiple times, I still have difficulties seeing exactly how she does what she does. Moden, her 2017 collection of poetry, follows Monster Poems (2013) and Morbus (2015) as the final volume in a loose trilogy. All three poems are about specific phenomena, united by theme, not by form.

Monster Poems is about monsters. Yes, pop cultural monsters, but also the monsters in us, the ways we can become monstrous. It’s about the threat of violence without and within. And all that is nice – but most of the poems contain a core of clarity, a discourse about female identity. “We Eves, all of us, I fear / we are replaceable” she writes in one poem, in another poem she marries Plath to Norman Bates, and in yet another poem, the big bad wolf comes to Little Red Riding Hood, opens his pants and tells her: “Reach Inside,” until eventually, she learns how to shoot, and kill, and where to bury the bodies. Nora Gomringer’s poems take no prisoners, but what I found most fascinating the first time I read Monster Poems was that language. It was loose and colloquial, but constantly tightened by a sense of form and art, with words often turned into an arch tone, but for once, it didn’t send me to the shelf to find the source. The source was right there.

Monster Poems is about monsters. Yes, pop cultural monsters, but also the monsters in us, the ways we can become monstrous. It’s about the threat of violence without and within. And all that is nice – but most of the poems contain a core of clarity, a discourse about female identity. “We Eves, all of us, I fear / we are replaceable” she writes in one poem, in another poem she marries Plath to Norman Bates, and in yet another poem, the big bad wolf comes to Little Red Riding Hood, opens his pants and tells her: “Reach Inside,” until eventually, she learns how to shoot, and kill, and where to bury the bodies. Nora Gomringer’s poems take no prisoners, but what I found most fascinating the first time I read Monster Poems was that language. It was loose and colloquial, but constantly tightened by a sense of form and art, with words often turned into an arch tone, but for once, it didn’t send me to the shelf to find the source. The source was right there.

The second book in the trilogy, Morbus, was about illness, death, and, generally, the fallibility of our bodies. In it, Gomringer’s language is just right, just hard and clean enough to manage a tightrope walk that moves you but never drops you into sentimentality. In a poem, which I think is about depression, she answers a question. “How would you describe this state?” and in three tercets, she offers three descriptions per stanza, one per line. She starts with “a black dog,” the common way to describe it, but moves on, and eventually we get “these questions of leather,” and finally, “the body in space.” The poem, built on repetition, varies its theme, introduces musical elements, plays with the various elements of its structure, including a final, completely dissolved tercet. At the same time, it offers a moving, stark evocation of emotional distress. It’s curious. It was published roughly around the same time as Jan Wagner’s book, and like his book, she is playful, clever, erudite and allusive, but unlike Wagner’s dull banalities, Morbus is vivid with something to say.

The second book in the trilogy, Morbus, was about illness, death, and, generally, the fallibility of our bodies. In it, Gomringer’s language is just right, just hard and clean enough to manage a tightrope walk that moves you but never drops you into sentimentality. In a poem, which I think is about depression, she answers a question. “How would you describe this state?” and in three tercets, she offers three descriptions per stanza, one per line. She starts with “a black dog,” the common way to describe it, but moves on, and eventually we get “these questions of leather,” and finally, “the body in space.” The poem, built on repetition, varies its theme, introduces musical elements, plays with the various elements of its structure, including a final, completely dissolved tercet. At the same time, it offers a moving, stark evocation of emotional distress. It’s curious. It was published roughly around the same time as Jan Wagner’s book, and like his book, she is playful, clever, erudite and allusive, but unlike Wagner’s dull banalities, Morbus is vivid with something to say.

This balance, between looseness and tightness – it’s hard to get right, and Moden is, in many ways, the crowning achievement of this method. In the poem “Maybelline 306” she invents the word “Fure,” a portmanteau of “Furie” and “Hure” (fury and whore), but before you get into the beautiful anger of this poem, you notice that its musical theme is set by an unexpected inversion in the second line which is, I think the essential moment that holds the whole poem together, this moment of tense formal focus. I mean this is obviously fitting since the whole book is about, loosely, the topic of fashion. Gomringer interrogates the way we interact with fashion, but most of all, the way the female body is made to fit the demands of fashion. Among these is the infamous practice of breaking and bending young girls’s feet to make them more elegant. The poem on the topic, “Lotus,” explains that the rules for this practice are written by people who are in love. And after explaining the method, she turns around at the end of the poem, and offers, in a very Brechtian tone, a connection to our time. Speaking of Brecht: maybe it’s just me, but I detect his tone not infrequently in this book, which is fascinating. This book’s lines and words and turns are sharper, more cutting, less patient than the previous books. It elevates the whole collection. To me, the book’s central poem is called Elfriede Gerstl. Gerstl was an Austrian writer and a holocaust survivor – but the poem doesn’t dwell on that. It assumes we know, it assumes we know this woman and her strength and her past. The centerpiece of the poem is a meeting between the speaker and Gerstl. I think it’s the central poem because Gerstl’s own work has connections to the way Moden works. In particular Gerstl’s stunning autobiographical text Kleiderflug, a book that contains a long poem, shorter and longer pieces of prose. In Gerstl, Gomringer finds a feminist who writes about fashion however indirectly, who, like Gomringer, is part of a larger literary scene (among Gerstl’s friends was Konrad Bayer), and who has a steely feminine strength that also imbues Gomringer’s books.

Moden is, I think, Gomringer’s best work so far, but she’s written a lot of good books, books that count, books that have to be counted. She belongs among the great poets writing in German right now, the likes of Paulus Böhmer, Sabine Scho and Friederike Mayröcker.

*

As always, if you feel like supporting this blog, there is a “Donate” button on the left and this link RIGHT HERE. 🙂 If you liked this, tell me. If you hated it, even better. Send me comments, requests or suggestions either below or via email (cf. my About page) or to my twitter.)

So I

So I  Honestly, if this wasn’t partially science fiction, I wouldn’t have reacted negatively to its 1950s view of gender roles at all – if you are in the habit of reading fantasy novels, particularly epic fantasy, you know that this kind of thing is to be expected. Fantasy doesn’t usually, in my reading experience, enlarge the pool of possibilities in quite the same way as science fiction does. And All the Birds in the Sky downright teases us with its allusions to Donna Haraway, Deleuze and other theories of change, dissolution and new formations. There are so many possibilities, so much potential – the same thing that bothered me about the Luc Besson movie – and Charlie Jane Anders picks the most boring one, boring, that is, from a SciFi point of view. As fantasy, it mines a trope that works extremely well. Fantasy and romance are a great combination – with a lot of room to maneuver, too. Even in mainstream fantasy, one sometimes gets something not as GOP-approved straight as this one (Jen Williams, in her fantasy novels, has a remarkable hand at sketching gay attraction, for example), but let’s be fair – this is the norm. And it’s so well executed by Anders. Trust me, if you’re looking for romance, this is right up your alley. Not to mention that Anders is extremely skilled at writing erotic scenes. The whole package is wildly engaging. I have a weak spot for romance in fiction and on screen and boy did this novel deliver. Anders manages to pace her two storylines, one of the war between science and magic and the other one of the love story between her protagonists, extremely well, so that as one comes together slowly, haltingly, so does the other, and each story’s ebb and flow is mirrored on the other level, until the dramatic conclusion, which feels extraordinarily satisfying.

Honestly, if this wasn’t partially science fiction, I wouldn’t have reacted negatively to its 1950s view of gender roles at all – if you are in the habit of reading fantasy novels, particularly epic fantasy, you know that this kind of thing is to be expected. Fantasy doesn’t usually, in my reading experience, enlarge the pool of possibilities in quite the same way as science fiction does. And All the Birds in the Sky downright teases us with its allusions to Donna Haraway, Deleuze and other theories of change, dissolution and new formations. There are so many possibilities, so much potential – the same thing that bothered me about the Luc Besson movie – and Charlie Jane Anders picks the most boring one, boring, that is, from a SciFi point of view. As fantasy, it mines a trope that works extremely well. Fantasy and romance are a great combination – with a lot of room to maneuver, too. Even in mainstream fantasy, one sometimes gets something not as GOP-approved straight as this one (Jen Williams, in her fantasy novels, has a remarkable hand at sketching gay attraction, for example), but let’s be fair – this is the norm. And it’s so well executed by Anders. Trust me, if you’re looking for romance, this is right up your alley. Not to mention that Anders is extremely skilled at writing erotic scenes. The whole package is wildly engaging. I have a weak spot for romance in fiction and on screen and boy did this novel deliver. Anders manages to pace her two storylines, one of the war between science and magic and the other one of the love story between her protagonists, extremely well, so that as one comes together slowly, haltingly, so does the other, and each story’s ebb and flow is mirrored on the other level, until the dramatic conclusion, which feels extraordinarily satisfying. But to get back to why this book doesn’t use Haraway in the way you’d expect – it’s not just the technological parts that are augmenting. The natural – regrettably gendered female, as technology was gendered male – part of the equation is also about augmentation, and about becoming more, doing more, understanding more. The initial augmentation, the mirror of the tiny time jump I mentioned, is the ability to talk to animals, but not fluently, at will and at all times, but a stubborn, halting, difficult ability that could, in some ways, be seen as an augmentation of human empathy, human abilities to understand animals through gestures, tone etc. Making this ability this inaccessible, and hard to use, was an extraordinary authorial decision, that doesn’t fit the usual smooth discoveries of magic. Often, while actually using magic skill is shown to be hard, fantasy novels treat the discovery of mere magical ability like the discovery of someone, thrown into water, that they can, indeed, breathe under water. This decision, and several others, show us a writer who has done some careful thinking about genre and how it works and how it is usually presented. It is such a shame, and such a bummer that Charlie Jane Anders decided to stop there, and thus meshed this intelligent careful use of tropes with this medieval view of gender roles, not to mention class or race. Maybe she kept to 1950s attitudes because of the enormous colorful way the whole book works. I mean it’s so much fun, even in the dramatic parts.

But to get back to why this book doesn’t use Haraway in the way you’d expect – it’s not just the technological parts that are augmenting. The natural – regrettably gendered female, as technology was gendered male – part of the equation is also about augmentation, and about becoming more, doing more, understanding more. The initial augmentation, the mirror of the tiny time jump I mentioned, is the ability to talk to animals, but not fluently, at will and at all times, but a stubborn, halting, difficult ability that could, in some ways, be seen as an augmentation of human empathy, human abilities to understand animals through gestures, tone etc. Making this ability this inaccessible, and hard to use, was an extraordinary authorial decision, that doesn’t fit the usual smooth discoveries of magic. Often, while actually using magic skill is shown to be hard, fantasy novels treat the discovery of mere magical ability like the discovery of someone, thrown into water, that they can, indeed, breathe under water. This decision, and several others, show us a writer who has done some careful thinking about genre and how it works and how it is usually presented. It is such a shame, and such a bummer that Charlie Jane Anders decided to stop there, and thus meshed this intelligent careful use of tropes with this medieval view of gender roles, not to mention class or race. Maybe she kept to 1950s attitudes because of the enormous colorful way the whole book works. I mean it’s so much fun, even in the dramatic parts.

I love Nina Allan. You can read my review of her debut novel The Race

I love Nina Allan. You can read my review of her debut novel The Race