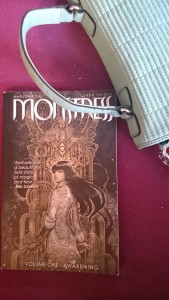

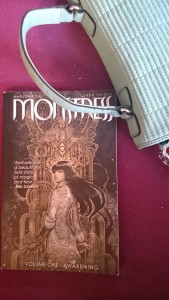

Liu, Marjorie and Sana Takeda (2016), Monstress, Vol. 1, Image Comics

ISBN 978-1632157096

Gibson, Claire, Sloane Leong and Marian Churchland (2016), From Under Mountains, Vol. 1, Image Comics

ISBN 978-1632159441

Marjorie Liu is slowly but surely growing into one of the mainstream comic industry’s most interesting figures, at least for me. She is not one of the steady writers, who write creator owned or licensed titles every year, but she’s also not one of those novelists who dip a toe into comic books here and there like Brad Meltzer or China Mieville. Liu has only a few titles to her name, but they are all important and worth reading, working with Marvel characters like X-23 (who is the new Wolverine in the current line of Marvel comics) and the X-Men (where she engineered the first gay wedding). This year, she wrote Monstress, a creator owned comic full of gorgeousness and brutality for Image comics that I would consider one of the four most beautiful and original comics to come out of mainstream comics this year, two of which I will review here. The second one under review is From Under Mountains, co-written by Claire Gibson and Marian Churchland. From Under Mountains is a comic by a writer and artist who I never heard of and I don’t remember what made me preorder the trade, but I am very glad I did, because its story of war and peace, of spirits and men, is worth reading and rereading. Both it and Monstress have created their own mythology, both of them based in fantasy worlds other than the typical European medieval environments we usually find. And both comics are true collaborations between writers and artists that found a unique visual language for a story that is complex but also as simple as any myth is. Sana Takeda’s sumptuous, rich art, which barely requires Liu’s dialog, is just as essential for Monstress as Sloane Leong’s angular lines and flat colors are for From Under Mountains. Neither comic is without flaws, but I recommend both very strongly.

Marjorie Liu is slowly but surely growing into one of the mainstream comic industry’s most interesting figures, at least for me. She is not one of the steady writers, who write creator owned or licensed titles every year, but she’s also not one of those novelists who dip a toe into comic books here and there like Brad Meltzer or China Mieville. Liu has only a few titles to her name, but they are all important and worth reading, working with Marvel characters like X-23 (who is the new Wolverine in the current line of Marvel comics) and the X-Men (where she engineered the first gay wedding). This year, she wrote Monstress, a creator owned comic full of gorgeousness and brutality for Image comics that I would consider one of the four most beautiful and original comics to come out of mainstream comics this year, two of which I will review here. The second one under review is From Under Mountains, co-written by Claire Gibson and Marian Churchland. From Under Mountains is a comic by a writer and artist who I never heard of and I don’t remember what made me preorder the trade, but I am very glad I did, because its story of war and peace, of spirits and men, is worth reading and rereading. Both it and Monstress have created their own mythology, both of them based in fantasy worlds other than the typical European medieval environments we usually find. And both comics are true collaborations between writers and artists that found a unique visual language for a story that is complex but also as simple as any myth is. Sana Takeda’s sumptuous, rich art, which barely requires Liu’s dialog, is just as essential for Monstress as Sloane Leong’s angular lines and flat colors are for From Under Mountains. Neither comic is without flaws, but I recommend both very strongly.

The first page from “Monstress.” Protagonist gets sold off in a slave auction, naked and without an arm.

Monstress, despite the adorable young girl on the cover, is brutal. Its story is a rough retelling of the aftermath of colonialism, as it happens in our world, but heightened with myth and metaphor. Liu’s story is set at the frontline of an uneasy truce between humans and a world of magical beings, the Arcanic. The book’s events are informed by the brutal war that preceded the truce, with a horrifying calamity forcing humans to accept a temporary peace. Humans are superior in every way to the retreating world of magical beings, but the unspecified calamity has convinced humans that the magical army possesses a terrible weapon that they will deploy with unspeakable ruthlessness. The basic opposition of modernity and myth has played out in many stories and movies, but I’ve never seen it expressed in such a physical, grounded way. Liu’s characters are former or current soldiers. They bear the scars, inside and out, of war, and the traumas thereof. The politics of the world Liu portrays are full of shifting loyalties and betrayals – the horrors of war makes people change sides, hide secrets and offer cruel compromises. The most convincing element, however, is the physicality of it all. Like a handful of good writers, Liu’s concept of magic involves the bodies of its practitioners. Magic is an ability that is bred into people, it is in their blood, and using it is a physical skill. So far, so common. Yet Liu, writing a world of realpolitik and brutal war, follows through with her ideas, and invents a specialized cadre among humans, the Cumaea, the so-called nun-witches, who extract material from the magical beings through various methods, none of them pleasant. People lose limbs, by and by, to satisfy the appetite of the voracious human military apparatus, which is increasingly dependent on its magical cadre.

A temple of the Ancients from “Monstress”

It’s easy to see these elements, as I said, as metaphors for acts undertaken by colonial powers in our world. The greed for knowledge and the piecemeal devouring of the native people are framed in ways that make them enormously fitting, and makes much of the book’s story ride piggyback on our cultural memories of war and colonialism. There is an emotional narrative, but the book only occasionally touches on it, with the biggest revelation coming as a cliffhanger at the book’s end. The main impact is, so to say, political. It makes us feel the cruelty and brutality of slavery, genocide and colonialism. Yet Liu interestingly balances these metaphorical effects, where she blends a thing in our world with a similar (but different) thing in the world of the book, with clashing effects, such as her interrogation of the role of women in our histories. Liu’s book is centered completely on its female characters, which has interesting implications, as has her use of the trope of the witch. Sana Takeda’s art is more than just helpful in all of this. She creates an overwhelmingly decadent visual language for the book, replete in browns and blues and gold. The décor seems sometimes Asian, I think, without really using orientalist stereotypes. It draws from multiple sources including fin de siècle decadence. It is impossible to express the enormity of Takeda’s achievement, who creates full landscapes and buildings, deep in color and rich in detail. Nothing is neglected, everything has the patina of history. Going through the book’s amazing art, you get the feeling that Liu had to write a story as harsh and impactful as she did, just to keep up with the extraordinary power of Takeda’s art nouveau panels. Takeda’s art mirrors the complicated strategies of metaphoricity that Liu pursues in her writing by offering art that is both recognizable and alien, giving us details that remind us of things we know, and elements seemingly plucked straight from a drawing room in 1900 in Paris or Shanghai.

Monstress is, thus, both beautifully disorienting and gloriously immersive. Just so we’re clear: it’s not a perfect book. Liu’s dialog is nowhere near as good as Takeda’s art and the contrast is sometimes not entirely pleasant, and Takeda’s art forces the book into a very slow pace, with its preference for big, immersive panels rather than quick story-oriented smaller sequences. Liu’s decision to drop us into medias res without long expositions adds to the book’s atmosphere, but also gives the reader an impression of having to catch up sometimes. But these are small quibbles in an overall greatly entertaining book. Small quibbles are also the only things I can mention on the negative side when it comes to From Under Mountains. I have not heard of any of its creators up until I read the comic, so the book’s quality took me by surprise. Much as Monstress, it does not offer any slow world building at the start, throwing us right in the middle of a court intrigue, a wizard’s scheme and the aftermath of a war, expecting us to catch up and add up all the elements to a coherent background. The writing is much sharper than Liu’s, but the story, despite its intrigues and complications, is simpler and not as complex as Liu’s, because Claire Gibson and Marian Churchland are not as interested in creating a similarly complex web of myth and reality, history and fantasy as Liu did. This may be due to the fact that From Under Mountains is a spin-off of sorts from a creative project masterminded by Brandon Graham, one of comic’s most original writers, whose run on Prophet is a breathtakingly brilliant science fiction comic. I have not read any comics from that project called 8House, since none have been collected into trades yet, but if Graham’s past work is any indication, they won’t be simple. Thus, it stands to reason From Under Mountains was conceived as a simpler tale told in a more turbulent universe. I don’t know. In any case, the simpler structure of the book is not a bad thing. And it just means less complicated than the byzantine world of Monstress. Gibson and Churchland have written a world that is not without its own complications and difficulties.

Monstress is, thus, both beautifully disorienting and gloriously immersive. Just so we’re clear: it’s not a perfect book. Liu’s dialog is nowhere near as good as Takeda’s art and the contrast is sometimes not entirely pleasant, and Takeda’s art forces the book into a very slow pace, with its preference for big, immersive panels rather than quick story-oriented smaller sequences. Liu’s decision to drop us into medias res without long expositions adds to the book’s atmosphere, but also gives the reader an impression of having to catch up sometimes. But these are small quibbles in an overall greatly entertaining book. Small quibbles are also the only things I can mention on the negative side when it comes to From Under Mountains. I have not heard of any of its creators up until I read the comic, so the book’s quality took me by surprise. Much as Monstress, it does not offer any slow world building at the start, throwing us right in the middle of a court intrigue, a wizard’s scheme and the aftermath of a war, expecting us to catch up and add up all the elements to a coherent background. The writing is much sharper than Liu’s, but the story, despite its intrigues and complications, is simpler and not as complex as Liu’s, because Claire Gibson and Marian Churchland are not as interested in creating a similarly complex web of myth and reality, history and fantasy as Liu did. This may be due to the fact that From Under Mountains is a spin-off of sorts from a creative project masterminded by Brandon Graham, one of comic’s most original writers, whose run on Prophet is a breathtakingly brilliant science fiction comic. I have not read any comics from that project called 8House, since none have been collected into trades yet, but if Graham’s past work is any indication, they won’t be simple. Thus, it stands to reason From Under Mountains was conceived as a simpler tale told in a more turbulent universe. I don’t know. In any case, the simpler structure of the book is not a bad thing. And it just means less complicated than the byzantine world of Monstress. Gibson and Churchland have written a world that is not without its own complications and difficulties.

full page from “From Under Mountains”

At its center are three characters, whose stories intersect: Lady Elena, daughter of the Lord of Karsgate, Tomas Fisher, a war hero with a dark secret past and a present full of debauchery and shame. The final protagonist, bleeding through the stories, connecting them, is a young thief who one night witnesses Lady Elena’s brother, the heir to Karsgate, get murdered by a spirit. From this murder, the three stories fan out. An impending war has to be prevented, the murderous spirit needs to be caught and personal demons need to be encountered and dealt with. Like Monstress, Gibson, Leong and Churchwell work with a large backdrop of history and intrigue and have no exposition to deal with any of it. In fact, the broader politics of the realm, with its apparently incapacitated king, its marriage policies and its way of dealing with supernatural threats, is barely touched upon in the pages of the first volume, simplifying much. Indeed, the clarity of the art and the less overwhelming politics of the book may give From Under Mountains an appearance of simplicity, but Gibson and Churchland approach narrative almost associatively. The three protagonists and some side characters slip in and out of their story so that when one of these stories, the arc of the Lord of Karsgate, is somewhat resolved, there’s a great feeling of narrative tension being released, with a myriad of other threads still in the air. The complicated arrangement of the protagonists’s stories makes for compelling reading in a trade but I cannot honestly imagine how this worked for readers of individual issues. The series appears to be on a hiatus for now, and if that had anything to do with sales, I can guess why. Much as with Monstress (and Prophet), this book appears to reap the benefits of a less tight editorial reign. From Under Mountains reads and looks like a completely realized artistic vision. The story is excellently orchestrated, and the dialog is much better – moreover, the book frequently contains silent panels, sometimes for several pages at a time, never losing narrative tension.

Silent full page vision from “From Under Mountains”

Much as with Monstress‘s Sana Takeda, this book is unthinkable without Sloane Leong’s art. It mirrors the flow of the narrative, it sometimes provides the book’s only language and overall dominates the whole book. Leong uses panels very freely, using the whole page for her effects. All pages are set in specific pastel hues, and the space between panels, when there’s such space, is colored in that hue so as to increase the immersive effect. Leong’s control of pace is masterful. Her broad, flat art is very static, but she uses panels within panels and blending with other panels to create time and focuses on attention as needed. Whereas Takeda in Monstress prefers big splashy pages deep and rich in detail, Leong’s backgrounds are sparse, but the artist constantly zooms in on small details, giving panels to hand gestures, flowers, flying insects, creating a story that draws you in without overwhelming you. As you can tell, I clearly lack the vocabulary or training for these descriptions, but suffice to say that visually, From Under Mountains is at least as virtuoso a performance as Monstress. And this doesn’t even include the attention lavished on dresses (there is a primer in the back about the different dresses for the different classes of people in the book, from peasants to nobles) and presentation. The way the book presents gender and race, visually, is intriguing, and the creative team appears to have decided to move some of its ideas in that department onto the visual level rather than have a disquisition on those ideas in the story which is exciting but conventional. If you’ve read mainstream fantasy comics these days, the story may have reminded you, for example, of Anthony Johnston’s very good Umbral, but whereas Johnston’s collaborator Christopher Mitten is fairly conventional (if very good), the end result of From Under Mountains is much more unique. This makes it so puzzling (and intriguing to see, on the comic’s final page, that the next trade/issues with end Leong’s run on the book and Gibson will continue with a new artist.

Anyway. If you trust me, you should go read these two books. You’re almost certainly not going to regret it.

*

As always, if you feel like supporting this blog, there is a “Donate” button on the left and this link RIGHT HERE.  If you liked this, tell me. If you hated it, even better. Send me comments, requests or suggestions either below or via email (cf. my About page) or to mytwitter.)

If you liked this, tell me. If you hated it, even better. Send me comments, requests or suggestions either below or via email (cf. my About page) or to mytwitter.)

Have a great 2017 everyone. I’m listening to an Otis live records right now, drinking a lovely gin. Who knows how long I will be around, any of us really. Have a drink on me, on you and the new year.

Have a great 2017 everyone. I’m listening to an Otis live records right now, drinking a lovely gin. Who knows how long I will be around, any of us really. Have a drink on me, on you and the new year.

So after posting

So after posting