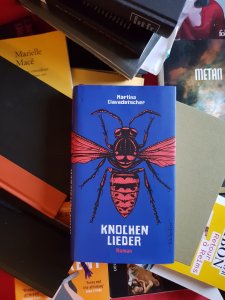

Clavadetscher, Martina (2017), Knochenlieder, Edition Bücherlese

ISBN 9783906907017

Sometimes a book is so surprisingly good that you stop reading and go online to look up what other books the author has written and how on earth this is the first time you read their work. At least for me, this is sometimes the case. This happened to me when I read Martina Clavadetscher’s debut novel Knochenlieder, a novel about inheritance, language, uncertain futures and how communities persevere. This is a very good book. It was shortlisted for the 2017 Swiss Book Award and should have won it, too. Clavadetscher employs all kinds of registers, from poetry to cyberpunk, from JG Ballard to fairy tales. Her novel, the title of which can be translated as “Bone Songs,” is part of the current wave of German-language dystopias, but she manages to produce a text that is both science fiction – and not. There are portions that seem a bit off as science fiction, strangely anachronistic discussions of digital matters that are supposed to take place roughly 60 years in the future, but sound outdated today. But Clavadetscher incorporates these anachronisms as a gesture, as an element of the text that tells us that this isn’t really about the future. Knochenlieder is about the linguistic way we construct the future, the way we conceive and shift our sense of home, our sense of ourselves. In this, Clavadetscher ressembles no writer as much as JG Ballard, whose work is echoed all over Knochenlieder. Ballard had also always been uncomfortable with suggestions that he wrote prescient literature. Ballard’s work engages our collective memories as humans, and the collective memory of life on earth. Clavadetscher’s novel is more personal, and she doesn’t appear to subscribe to complicated theories such as those that undergird Ballard’s novels, but it has been awhile since I’ve read a novel about the future that so powerfully engages our present and past instead. And on top of all this, Clavadetscher’s language, despite the occasional slip into sentimentality, is clever, musical and sharp – and should be fairly easy to translate because she achieves all that with a more limited vocabulary than you’d expect of what is essentially a novel in verse. Knochenlieder is always a balancing act – had it been written with less skill, it could have failed in numerous ways. Instead, it seems very successful in what it attempts to do. A good writer. A good book. Read it. Translate it.

Sometimes a book is so surprisingly good that you stop reading and go online to look up what other books the author has written and how on earth this is the first time you read their work. At least for me, this is sometimes the case. This happened to me when I read Martina Clavadetscher’s debut novel Knochenlieder, a novel about inheritance, language, uncertain futures and how communities persevere. This is a very good book. It was shortlisted for the 2017 Swiss Book Award and should have won it, too. Clavadetscher employs all kinds of registers, from poetry to cyberpunk, from JG Ballard to fairy tales. Her novel, the title of which can be translated as “Bone Songs,” is part of the current wave of German-language dystopias, but she manages to produce a text that is both science fiction – and not. There are portions that seem a bit off as science fiction, strangely anachronistic discussions of digital matters that are supposed to take place roughly 60 years in the future, but sound outdated today. But Clavadetscher incorporates these anachronisms as a gesture, as an element of the text that tells us that this isn’t really about the future. Knochenlieder is about the linguistic way we construct the future, the way we conceive and shift our sense of home, our sense of ourselves. In this, Clavadetscher ressembles no writer as much as JG Ballard, whose work is echoed all over Knochenlieder. Ballard had also always been uncomfortable with suggestions that he wrote prescient literature. Ballard’s work engages our collective memories as humans, and the collective memory of life on earth. Clavadetscher’s novel is more personal, and she doesn’t appear to subscribe to complicated theories such as those that undergird Ballard’s novels, but it has been awhile since I’ve read a novel about the future that so powerfully engages our present and past instead. And on top of all this, Clavadetscher’s language, despite the occasional slip into sentimentality, is clever, musical and sharp – and should be fairly easy to translate because she achieves all that with a more limited vocabulary than you’d expect of what is essentially a novel in verse. Knochenlieder is always a balancing act – had it been written with less skill, it could have failed in numerous ways. Instead, it seems very successful in what it attempts to do. A good writer. A good book. Read it. Translate it.

I mean, this is not to say that the book doesn’t have blind spots, but its clever construction makes you at least question whether what you see are indeed actual blind spots or whether you diagnosed something intentional as a blind spot. The novel has three parts, set in a chronological sequence. The first part is set in 2020, so in the very near future, in a small commune of sorts, a group of people who decided to escape the increasing awfulness of the world by going mostly off the grid. This commune is a group of families, who informally renamed themselves after colors and painted their houses that way. Clavadetscher combines different things in her commune. They are off the grid, but in a very specific way that distrusts not just the increasingly unsafe world (there’s a war going on outside, we eventually learn), but they also fit a kind of state of mind that is common today too: people who distrust modern medicine, focus on “natural” remedies and solutions. If you look at these communities today, they are often white, privileged, and focusing on notions of family and heritage that are politically unpleasant sometimes. When the “Green” family, long unable to conceive, manage to engender a pregnancy with the help of medicine, other members of the community attack them for introducing the “stachelkind” – a barbed or thorned child, an unnatural, cursed child. This phrasing recalls, in fact, the recent-ish comments by Sibylle Lewitscharoff, an important contemporary German novelist. In a speech in 2014, she referred to the abominations of children conceived in unnatural ways, like in vitro fertilization. She called them “Halbwesen,” chimeras: “They are not quite real in my eyes, but dubious creatures, half human, half artificial Godknowswhat.” Since Knochenlieder was originally written in 2015, and its themes overlap with some themes of Lewitscharoff’s novels, it’s hard not to see a connection. Mind you, I think the scope of criticism is wider than one novelist: it’s about a problematic mind-set.

Clavadetscher’s choices here are intriguing. Setting up such a community could have made her novel approach fiction like Sarah Hall’s good The Carhullan Army, stories about communities off the grid, often governed by a fundamentalist secular ideology of sorts. Instead, she barely touches on the ideology, thus asking us to implicitly associate them with the groups and ideologies we already know. She focuses on the human aspects, because ultimately, her novel is about how we relate to one another and how we make a home with one another. Additionally, the science fiction doesn’t end with this (near-)future community. The more science fictional elements, including some not-quite-right technobabble, follow this. Doing this creates a tension. On the one hand, the second part, set in a metropolis, among hackers and computers, makes the simple, poetic, pastoral first part resonate as a kind of ideal, idyllic place before modernity breaks in. At the same time, we are shown that it is already broken – not by modernity but by lack of empathy, love and community spirit. Clavadetscher evades simple dichotomies, lifting her discourse into language itself.

Clavadetscher’s choices here are intriguing. Setting up such a community could have made her novel approach fiction like Sarah Hall’s good The Carhullan Army, stories about communities off the grid, often governed by a fundamentalist secular ideology of sorts. Instead, she barely touches on the ideology, thus asking us to implicitly associate them with the groups and ideologies we already know. She focuses on the human aspects, because ultimately, her novel is about how we relate to one another and how we make a home with one another. Additionally, the science fiction doesn’t end with this (near-)future community. The more science fictional elements, including some not-quite-right technobabble, follow this. Doing this creates a tension. On the one hand, the second part, set in a metropolis, among hackers and computers, makes the simple, poetic, pastoral first part resonate as a kind of ideal, idyllic place before modernity breaks in. At the same time, we are shown that it is already broken – not by modernity but by lack of empathy, love and community spirit. Clavadetscher evades simple dichotomies, lifting her discourse into language itself.

And indeed, the language of the novel is remarkable. Clavadetscher writes a prose that is lyrical, but not excessively so. She uses line breaks to speed up and slow down her narrative. It allows her to create palpable, sensuous scenes of action and seduction. Her language allows for a clear treatment of hallucinations as well as of realistic observations without really including a linguistic shift, there’s enough room in her language for both. She does, and it’s almost impossible not to, I think, with this kind of writing, sometimes slip into sentimentality as well as a kind of poeticism that echoes Günter Grass’s very specific phrasings extremely strongly. But those moments are an exception. Novels in verse are often either banal or horribly burdened by self-consciously poetic language. Clavadetscher’s prose has a purpose, there are muscles working under the surface, and the effect is extraordinary. One such effect is that the poetic and allusive style presents a kind of discursive “home,” a fixed point of emotional reference as the world described degrades into dystopian awfulness. As the novel slowly turns into the search of a daughter for her mother, Clavadetscher increases the amount of fairy tale motifs, enriching and affirming the book’s basic linguistic direction as the lingistic search for home starts corresponding to a narrative search for home. My intuition to search for a language based solution to some of the novel’s intricacies is confirmed, I think, by what I called “technobabble” in the novel’s middle section. The protagonist of the second section is a hacker, but written the way old people imagine hackers. It uses current vocabulary and offers a kind of hacking that we do now, and indeed have done for a while now. The novels and movies of the 1980s and early 1990s, though more mid-career Neal Stephenson than William Gibson, are clearly echoed in these lines, though brought slightly up to date. The 1995 movie Hackers, which isn’t actually that awful of a portrayal of hacking resonates throughout. In no way would hackers 60 years from now go about their business the way that is described in the book. However, I don’t think we’re supposed to read this as a realistic hard SF speculation. Yes, it sounds outdated for 2017 – but it’s supposed to sound that way, I suspect. The novel pushes its readers onto the level of language, allusion and discurse.

If I was reticent about plot details, it’s because the plot of the book is good fun, I think, and there’s no need to spoil it. Ultimately, Clavadetscher has written an engaging, intelligent book that is more original that the vast majority of contemporary literature in German, particularly the prize winning kind written by non-immigrant writers. The Swiss Book Award was won, eventually, by Jonas Lüscher’s most recent awful novel, one of many praised and shortlisted novels about male professors and their righteous ruminations. Knochenlieder doesn’t really add to important political discourses, despite alluding to a future with camps and wars. Nevertheless, there’s something at stake here, this is literature that takes risks, that is fun to read and sometimes disturbing to ponder. This is an unusual and exciting voice. Translate it already.

*

As always, if you feel like supporting this blog, there is a “Donate” button on the left and this link RIGHT HERE. 🙂 If you liked this, tell me. If you hated it, even better. Send me comments, requests or suggestions either below or via email (cf. my About page) or to my twitter.)

Pingback: My Year in Reviewing: 2017 | shigekuni.

Pingback: German Literature Month VII: Author Index – Lizzy's Literary Life