Otoo, Sharon Dodua (2015), Synchronicity, Edition Assemblage

With Illustrations by Sita Ngoumou

ISBN 978-3-942885-95-9

Otoo, Sharon Dodua (2012), The Things I am Thinking While Smiling Politely, Edition Assemblage

ISBN 978-3-942885-22-5

Is this German literature? Sharon Otoo is not a German writer. She is, according to her page and the book cover, “a Black British mother, activist, author and editor;” and both books under review are written in English. There is a German version of both, published more or less simultaneously by the same publisher, who is headquartered in Münster, in North-Rhine Westphalia in West Germany, but they have both been translated by a person other than the author (Mirjam Nuenning). Otoo lives and works in Germany and is involved in German debates on racism and refugees. She moved to Germany in 2006 and immediately became involved in activism involving blackness in Germany. I recommend reading this interview. This year, she won the Bachmannpreis for a brilliant story, written in German, which was clearly, to pretty much any competent observer, the best text in the competition, despite some excellent work by the other competitors. The two novellas under review are a cultural hybrid, written in English by a writer with English education and sensibilities, but set in Germany and informed by the sharp observations and brilliant details of a critically observant person living in this country. German literature written by Germans of German descent is pretty dull these days, with a few notable exceptions. Too much of it has been nurtured in the two big MFA mills, too much of it is blind, privileged pap with nothing at stake. Otoo’s books are brilliantly aware of traditions and contexts, of how assumptions and narratives intersect. Synchronicity is a near-allegorical tale of migration, community and adulthood and extends the promise of Otoo’s debut. The Things I am Thinking While Smiling Politely, a book about heartbreak, racism and migration. Both books are written with a sharp stylistic economy that never lapses into flatness, a skill that is as rare as it is commendable. If German literature is to have an interesting future, then it is not young writers writing clever postmodern 1000 page books with nothing at stake or MFA mill products with their self-congratulatory emptiness. It is writers with a migratory background who inject fresh energy and purpose into a literature that has grown rather tired. Otoo does not identify as a German writer but it is German literature that most stands to profit from her growing body of work.

Is this German literature? Sharon Otoo is not a German writer. She is, according to her page and the book cover, “a Black British mother, activist, author and editor;” and both books under review are written in English. There is a German version of both, published more or less simultaneously by the same publisher, who is headquartered in Münster, in North-Rhine Westphalia in West Germany, but they have both been translated by a person other than the author (Mirjam Nuenning). Otoo lives and works in Germany and is involved in German debates on racism and refugees. She moved to Germany in 2006 and immediately became involved in activism involving blackness in Germany. I recommend reading this interview. This year, she won the Bachmannpreis for a brilliant story, written in German, which was clearly, to pretty much any competent observer, the best text in the competition, despite some excellent work by the other competitors. The two novellas under review are a cultural hybrid, written in English by a writer with English education and sensibilities, but set in Germany and informed by the sharp observations and brilliant details of a critically observant person living in this country. German literature written by Germans of German descent is pretty dull these days, with a few notable exceptions. Too much of it has been nurtured in the two big MFA mills, too much of it is blind, privileged pap with nothing at stake. Otoo’s books are brilliantly aware of traditions and contexts, of how assumptions and narratives intersect. Synchronicity is a near-allegorical tale of migration, community and adulthood and extends the promise of Otoo’s debut. The Things I am Thinking While Smiling Politely, a book about heartbreak, racism and migration. Both books are written with a sharp stylistic economy that never lapses into flatness, a skill that is as rare as it is commendable. If German literature is to have an interesting future, then it is not young writers writing clever postmodern 1000 page books with nothing at stake or MFA mill products with their self-congratulatory emptiness. It is writers with a migratory background who inject fresh energy and purpose into a literature that has grown rather tired. Otoo does not identify as a German writer but it is German literature that most stands to profit from her growing body of work.

Synchronicity is a multi-layered, but straight-forward story of community and family. Everything else, all the magical realism, all the bells and whistles, are woven around this core. Blackness and migration is a tale of fighting to belong. In the much more knotty and fragmented Things I am Thinking…, the protagonist explains that, being “the only black girl in a London suburb” she “quickly leaned that trouble could be avoided if [she] acted white.” This thinking is continued and expanded upon in Synchronicity – while the first novella used the personal as a mirror and medium to reflect (and reflect upon) political aspects, combining heartbreak with thoughts of alienation, this second novella is more deliberate and careful in discussing migration by offering us a set of metaphors on the one hand, and tableau of characters who all relate to the protagonist along an axis of power and nationality. The more streamlined nature of the second book derives to a great part from the genesis of the book as a Christmas tale written in 24 daily installments and sent to friends and family. The idea of turning it into a book came later, which explains why the two novellas are so different in construction. Things I am Thinking… is written in fragments, with a narrator who keeps going back and forth in time, to reveal some things and hint at others. The chapters all start mid-sentence and each chapter is preceded by a “shrapnel,” an emotionally charged quote. The book only makes sense as a complete construction, there’s no way to write that kind of book by coming up with daily installments. And yet the linear nature of Synchronicity is also not a sign of Otoo’s development, because her Bachmannpreis-winning story is exceptionally well constructed, with cultural, historical and theoretical allusions coming together to create a story that is deceptively simple, a story that needed to be mapped out in advance. I suspect when we look at Otoo’s work in a few years, after she has written the novel that she’s writing now (and won the Chamisso-award that she’s practically a shoo-in for at this point) and edited some more books, that Synchronicity will stand out as a unique part of her oeuvre. An unusual work by a writer of uncommon talent.

Synchronicity is a multi-layered, but straight-forward story of community and family. Everything else, all the magical realism, all the bells and whistles, are woven around this core. Blackness and migration is a tale of fighting to belong. In the much more knotty and fragmented Things I am Thinking…, the protagonist explains that, being “the only black girl in a London suburb” she “quickly leaned that trouble could be avoided if [she] acted white.” This thinking is continued and expanded upon in Synchronicity – while the first novella used the personal as a mirror and medium to reflect (and reflect upon) political aspects, combining heartbreak with thoughts of alienation, this second novella is more deliberate and careful in discussing migration by offering us a set of metaphors on the one hand, and tableau of characters who all relate to the protagonist along an axis of power and nationality. The more streamlined nature of the second book derives to a great part from the genesis of the book as a Christmas tale written in 24 daily installments and sent to friends and family. The idea of turning it into a book came later, which explains why the two novellas are so different in construction. Things I am Thinking… is written in fragments, with a narrator who keeps going back and forth in time, to reveal some things and hint at others. The chapters all start mid-sentence and each chapter is preceded by a “shrapnel,” an emotionally charged quote. The book only makes sense as a complete construction, there’s no way to write that kind of book by coming up with daily installments. And yet the linear nature of Synchronicity is also not a sign of Otoo’s development, because her Bachmannpreis-winning story is exceptionally well constructed, with cultural, historical and theoretical allusions coming together to create a story that is deceptively simple, a story that needed to be mapped out in advance. I suspect when we look at Otoo’s work in a few years, after she has written the novel that she’s writing now (and won the Chamisso-award that she’s practically a shoo-in for at this point) and edited some more books, that Synchronicity will stand out as a unique part of her oeuvre. An unusual work by a writer of uncommon talent.

It is important to note what an incredible progress the author has made since her first novella, despite that book’s high quality. Things I am Thinking… is a dense realist book that is fairly low on allusion and high on clarity of observation. The prose is lean but effective throughout, sometimes leaning a bit towards the journalistic. The real achievement of the book, however, is not the writing or the observations, per se, it is the author’s skill of connecting various elements of her narrator’s life in meaningful but subtle ways. I am sure the author is aware of various aspects of political philosophy, from Foucault to Critical Race Studies, but she wears that knowledge lightly. This is the philosophical version of “show not tell.” The book’s story is about a Black woman who lives in Germany. She has broken up with her husband Till, who is also the father of her child. She has friends of various ethnicities and origins, among them refugees. She has increasingly become disillusioned with the reality of Germany, which is expressed particularly well in the narrator’s attitude towards her husband’s name

It is important to note what an incredible progress the author has made since her first novella, despite that book’s high quality. Things I am Thinking… is a dense realist book that is fairly low on allusion and high on clarity of observation. The prose is lean but effective throughout, sometimes leaning a bit towards the journalistic. The real achievement of the book, however, is not the writing or the observations, per se, it is the author’s skill of connecting various elements of her narrator’s life in meaningful but subtle ways. I am sure the author is aware of various aspects of political philosophy, from Foucault to Critical Race Studies, but she wears that knowledge lightly. This is the philosophical version of “show not tell.” The book’s story is about a Black woman who lives in Germany. She has broken up with her husband Till, who is also the father of her child. She has friends of various ethnicities and origins, among them refugees. She has increasingly become disillusioned with the reality of Germany, which is expressed particularly well in the narrator’s attitude towards her husband’s name

So it was a matter of great inspiration to me, meeting Till on my year abroad in Germany. Someone with a surname so unambiguously of the country he was born, raised and lived in that I thought: how sexy is that? And I knew I had to make it my own. This however didn’t stop other officially suited white ladies in cold offices from saying “Wie bitte?” and asking me to repeat myself – like they were disappointed because they had been expecting me to be called something resembling Umdibondingo or whatever. Several months after we were married, I discovered that “Peters” was also the surname of a German colonial aggressor and although I didn’t begin to hate it then, I stopped adorning myself with it.

Otoo pulls off a rare trick – her book is dense and cerebral, but it has a story to tell, as well as a narrative and political urgency. Everything in the book has a purpose and is connected to everything else, but it never feels like Otoo is simply having a postmodern game on. This is not the place to unravel all the book’s plotlines and trajectories, but suffice to say that she manages to see how the different ways power shapes and controls us intersect and collaborate. And her protagonist, who has learned to accommodate various demands of power, is now crashing against the walls of the well-built house of German racism and economics because her personal life implodes. The word “shrapnel” is well chosen for the quotes preceding the chapters because the impression I got reading the book was that heartbreak, a fundamental personal emotion, functions like a bomb that explodes in the middle of a lifetime of accomodation and struggle. The book itself, while not framed explicitly as a text written by the protagonist, feels like an attempt to assemble the shards of a life, where one betrayal has damaged personal, professional and social relationships.

The aspect of migration is not central to Things I am Thinking…. We learn that the protagonist is British, but migration is experienced more through the eyes of the refugees we encounter in the book like Kareem, of whom the author remarks that he “has this matter of fact, nothing-to-lose air about his person. Years of being an illegal immigrant in an unwelcoming country will do that to you, I guess.” Much of the alienation that we learn about is the kind that happens when you look foreign and live in a racist country:

The aspect of migration is not central to Things I am Thinking…. We learn that the protagonist is British, but migration is experienced more through the eyes of the refugees we encounter in the book like Kareem, of whom the author remarks that he “has this matter of fact, nothing-to-lose air about his person. Years of being an illegal immigrant in an unwelcoming country will do that to you, I guess.” Much of the alienation that we learn about is the kind that happens when you look foreign and live in a racist country:

Berlin is a place where anything goes, and you can wear whatever you like, but if you are a Black woman in the underground, be prepared to be looked up and down very very slowly. I cannot tell you how many times I have glanced down at myself in horror during such moments to check if my jeans were unzipped or if my dress was caught up in my underwear. White people look at me sometimes like I am their own private Völkerschau. Staring back doesn’t help. It counts as part of the entertainment. Entertainment.

We get hints sometimes as to how a hybrid identity can develop with migration, such as when the protagonist recounts the criticism her “auntie” leveled at her: “she was truly shocked when she first realized that I had not raised Beth to hand wash her own underwear every night.” The reason for “auntie”’s outrage is the question of identity: “just because she has a whitey father, doesn’t mean she’s not Ghanaian!” The protagonist is not so sanguine about these matters, more interested in negotiating a Black identity in Germany, dealing with the shifting fortunes of being married to someone named Peters, and with the difficulties of establishing trust and loyalties in this country when you’re viewed as foreign.

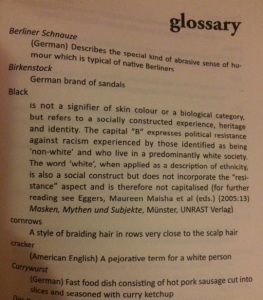

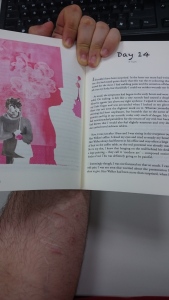

Synchronicity, on the other hand, is primarily dedicated to these questions of heritage and migration. There are basically two stories, layered one above the other, in the book. One, the surface-level story, is the one of Charlie Mensah, known as “Cee,” who is a graphic designer who, one day, starts to “lose” her colors. This is meant quite literally. For a couple of days, she stops being able to see certain colors, with one color absconding per day. Blue, red, green, etc., until just gray remains. The beautiful illustrations by Sita Ngoumou provide a lovely background to this contrast. This is challenging to Cee, who is a freelance designer, with a big and well-paid project coming up, and who has suddenly lost the use of one of her most important faculties. Eventually, however, the colors return, one by one, albeit in a different form. This, so far, is the story as a realist narrative would describe it. There are smaller plotlines woven into it, such as Cee falling in love, and her conflicts with her client, but basically, this is it. The other story is the one concerning heritage and identity. This loss of colors is not some disability, not some virus or sickness, it is a process of maturation that happens to all the women in her family. The “different form” that colors are regained in is what the author calls “polysense,” a special form of synesthesia. And this is not all that is different about the women in Cee’s family. They are also all women who don’t reproduce sexually. They are parthogenic, which, as Cee explains, “means we have children alone – that our bodies are designed to become pregnant completely by themselves.” This is not some science fictional theory, although it echoes such science fictional worlds as the planet Whileaway in Joanna Russ’ feminist classic The Female Man. Otoo, beyond the term, never goes into details, because this strange genetic heritage serves primarily as a metaphor for migration and alienation. The people in Cee’s family live alone. They raise their daughters to be independent and then, once they are adult, they push them out of the house and then let them fend for themselves. The maturation process to polysense, and the insistence on independence makes it hard for these women to establish personal bonds; thus, Otoo found a metaphor to reify something that has been part of immigrant experience for a long time.

Synchronicity, on the other hand, is primarily dedicated to these questions of heritage and migration. There are basically two stories, layered one above the other, in the book. One, the surface-level story, is the one of Charlie Mensah, known as “Cee,” who is a graphic designer who, one day, starts to “lose” her colors. This is meant quite literally. For a couple of days, she stops being able to see certain colors, with one color absconding per day. Blue, red, green, etc., until just gray remains. The beautiful illustrations by Sita Ngoumou provide a lovely background to this contrast. This is challenging to Cee, who is a freelance designer, with a big and well-paid project coming up, and who has suddenly lost the use of one of her most important faculties. Eventually, however, the colors return, one by one, albeit in a different form. This, so far, is the story as a realist narrative would describe it. There are smaller plotlines woven into it, such as Cee falling in love, and her conflicts with her client, but basically, this is it. The other story is the one concerning heritage and identity. This loss of colors is not some disability, not some virus or sickness, it is a process of maturation that happens to all the women in her family. The “different form” that colors are regained in is what the author calls “polysense,” a special form of synesthesia. And this is not all that is different about the women in Cee’s family. They are also all women who don’t reproduce sexually. They are parthogenic, which, as Cee explains, “means we have children alone – that our bodies are designed to become pregnant completely by themselves.” This is not some science fictional theory, although it echoes such science fictional worlds as the planet Whileaway in Joanna Russ’ feminist classic The Female Man. Otoo, beyond the term, never goes into details, because this strange genetic heritage serves primarily as a metaphor for migration and alienation. The people in Cee’s family live alone. They raise their daughters to be independent and then, once they are adult, they push them out of the house and then let them fend for themselves. The maturation process to polysense, and the insistence on independence makes it hard for these women to establish personal bonds; thus, Otoo found a metaphor to reify something that has been part of immigrant experience for a long time.

A better way, I suppose to frame it, is Axel Honneth’s innovative take on the subject of reification, where the process of recognizing the other is fundamental to the way our subjectivity is constructed and yet that recognition, which, as Butler writes, “is something achieved” that “emerge[s] first only after we wake from a more primary forgetfulness,” can be abandoned. The forgetting of recognition is, in Honneth’s reading, what. In classic terminology, we called reification. What does migration to to emotional recognition? How do we react when we migrate into places that see us as a constituting alterity, that use us to create their national and personal narratives. In Otoo’s slender and careful book, the answer, given for many generations of immigrants, is to retreat to a specific kind of subjectivity that rejects recognition. The parthogenetic reproduction is a perfect metaphor for that. But the tone of the book isn’t dark. Otoo, who works as an activist, imbues her novella with confidence in the future. Her migrants break free of this mold. Cee’s daughter refuses to accept the ways of her family and Cee herself sees changes in her and the world around her. She falls in love with a policeman who isn’t white, representing a fusion of her horizons with that of the country she migrated to. The most powerful description of the policeman is not the first time she sees him, it is a moment of recognition, which, for Honneth, is something that is part of maturation:

A better way, I suppose to frame it, is Axel Honneth’s innovative take on the subject of reification, where the process of recognizing the other is fundamental to the way our subjectivity is constructed and yet that recognition, which, as Butler writes, “is something achieved” that “emerge[s] first only after we wake from a more primary forgetfulness,” can be abandoned. The forgetting of recognition is, in Honneth’s reading, what. In classic terminology, we called reification. What does migration to to emotional recognition? How do we react when we migrate into places that see us as a constituting alterity, that use us to create their national and personal narratives. In Otoo’s slender and careful book, the answer, given for many generations of immigrants, is to retreat to a specific kind of subjectivity that rejects recognition. The parthogenetic reproduction is a perfect metaphor for that. But the tone of the book isn’t dark. Otoo, who works as an activist, imbues her novella with confidence in the future. Her migrants break free of this mold. Cee’s daughter refuses to accept the ways of her family and Cee herself sees changes in her and the world around her. She falls in love with a policeman who isn’t white, representing a fusion of her horizons with that of the country she migrated to. The most powerful description of the policeman is not the first time she sees him, it is a moment of recognition, which, for Honneth, is something that is part of maturation:

That policeman. I recognized him straight away this time because he had a particular kind of walk. Like he was happy to be walking at all. In fact, if I had to choose one word to describe his body language it would be: gratitude. That really fascinated me. I stared at him for quite some time as I walked towards him – he was in deep conversation with his white colleague. I could tell the colleague was white because his walk was altogether more sturdy and authoritarian. He placed his feet firmly onto the ground, each step conferring a heritage of legitimacy and ownership unto him.

The book is a Christmas story, which explains its optimism and lightness, but it also offers a literary third way between assimilation and rejection. Critical optimism, if you will. It is a unique quality that appears to be emerging in Otoo’s work. Things I am Thinking… is a much darker work, but the story that Otoo read at the Bachmannpreis walks the same line as Synchronicity does. I don’t think I’ve ever read quite the same kind of story in this country and I don’t think I have ever read a writer quite like Otoo.

At the Bachmannpreis (I had a short post on it last year here) the jury discussions of Otoo’s text and the one of Tomer Gardi, another exciting text read at the competition, as well as the contrast to the bland terrible awfulness of the texts read by Jan Snela, Julia Wolf, Isabelle Lehn or Astrid Sozio (who, slotted directly behind Otoo, read a spectacularly racist text) maybe shows where literature written and published in this country needs to turn. The comfortable and unnecessary tales of migrancy from a MFA-educated German mind do not add to the conversation and they do not produce good literature. That is a dead end, and nothing demonstrated that dead end as well as the comparison of the field with Sharon Otoo’s excellent text, and Otoo’s work in general.

At the Bachmannpreis (I had a short post on it last year here) the jury discussions of Otoo’s text and the one of Tomer Gardi, another exciting text read at the competition, as well as the contrast to the bland terrible awfulness of the texts read by Jan Snela, Julia Wolf, Isabelle Lehn or Astrid Sozio (who, slotted directly behind Otoo, read a spectacularly racist text) maybe shows where literature written and published in this country needs to turn. The comfortable and unnecessary tales of migrancy from a MFA-educated German mind do not add to the conversation and they do not produce good literature. That is a dead end, and nothing demonstrated that dead end as well as the comparison of the field with Sharon Otoo’s excellent text, and Otoo’s work in general.

*

As always, if you feel like supporting this blog, there is a “Donate” button on the left and this link RIGHT HERE. If you liked this, tell me. If you hated it, even better. Send me comments, requests or suggestions either below or via email (cf. my About page) or to my twitter.)